Stay Away from Comfort

Talking to Tono StanoTS (1960) about work, beauty and time as captured in his photographs in a major retrospective exhibition at the GHMP.

Q. You often refer to your work as research and exploration. What do you research?

TS. The essential thing is to find out who I am and to identify with myself. Everything else follows from that. I have realised that life equals energy plus time. When I was sixteen, at a secondary school in Bratislava, I found it essential to make time to live for myself; to do everything I could, to be able to freely use and work with time, which was a challenge under socialism. When I look back, I can say I have succeeded in doing so, which I consider the greatest achievement of my life so far. This means I can focus on my research and the relationships that come with the research. It‘s a matter of not getting stuck in anything that could control my mind, of not being fooled by delusive sludge. By attempts to influence the masses, which is what we see in the media or religion. It‘s about breaking away from anything that would lead me in a false direction. I want to be close to the truest version of what is happening in the world. I feel that I haven‘t exhausted any of my research topics. On the contrary, I keep opening more doors.

Q. Is work an obsession for you?

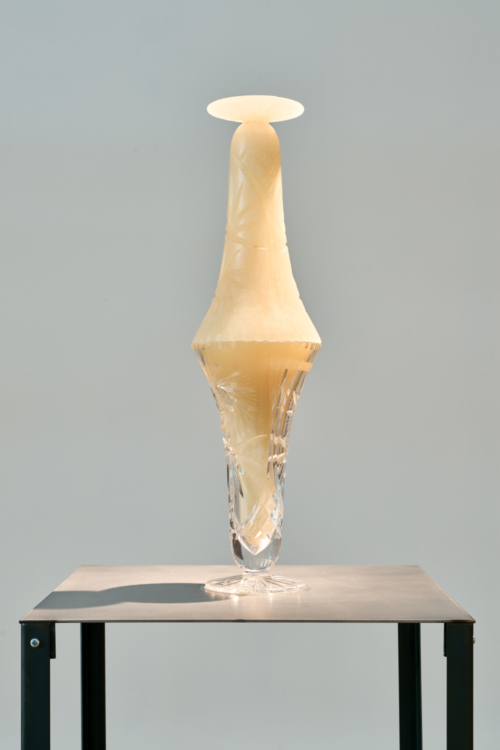

TS. The term „work“ isn‘t quite apt for what I do. One of my obsessions is that I like to use the energy that is lying around that bears a certain content. I bring it back to life. Right now, I‘m in the process of making furniture for my exhibition at GHMP. I consider the space in the Municipal Library the best, far and wide, even compared to anywhere abroad, I don‘t know a better place for my things. The only thing I’ve always missed there is being able to sit down and look into the space of the room. For a long time, I have been collecting, buying, discovering objects (sometimes they are just torsos) in my style, and that inspire me for further use. I have a farmhouse in South Bohemia that I use as a depository. One of its sections contains used and damaged tubular furniture in the functionalist style. I have already created several new things in the form of a couch. For example, I found a discarded produced by from the famous Brno company Vichr, plus some other parts. I made two chairs, almost thrones, for one of the gallery rooms of the Municipal Library. The furniture in the gallery will be equipped with castors, so it will be possible to move them. They will be original objects in the space. There will also be big cushions, and armrests. Comfort as a bonus to the exhibition. I‘ve made drawings that show what the furniture should look like, and I found a skilled welder who can put it together. When you endow obsession with experience, curiosity, intelligence and intuition, there is the chance of a satisfying result although it‘s not guaranteed at the outset. Look, I have one of the castors which will be used for the furniture on my table, here. Initially, it was impossible to find suitable castors. I ordered them and they came in a colour that was presented as grey, but it is actually purple. I don‘t have a good relationship with purple. So, now I have to do something about it.

Q. What kind of photos are you going to display?

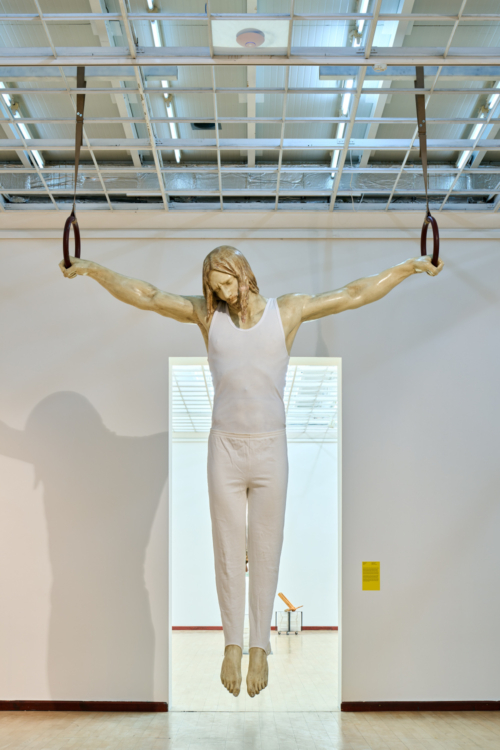

TS. I want to showcase things that are topical for me from different periods of time. I found it very useful if only because, after the exhibition, we are preparing a comprehensive monograph. For both the exhibition and the monograph, a summary of the work done so far is needed. A raster, or a mosaic has to be found so I can see what is possibly missing and what I could add. I am not interested in multiplying copies of my own work; each photograph should have its own reason. The photos for the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival will have a separate cubicle in the library’s gallery. As far as portraits are concerned, there will be a large portrait of the wild man František Vláčil, where the film director looks like a wolf, and a laughing Václav Havel, portrayed in an improvised studio at Hrádeček.

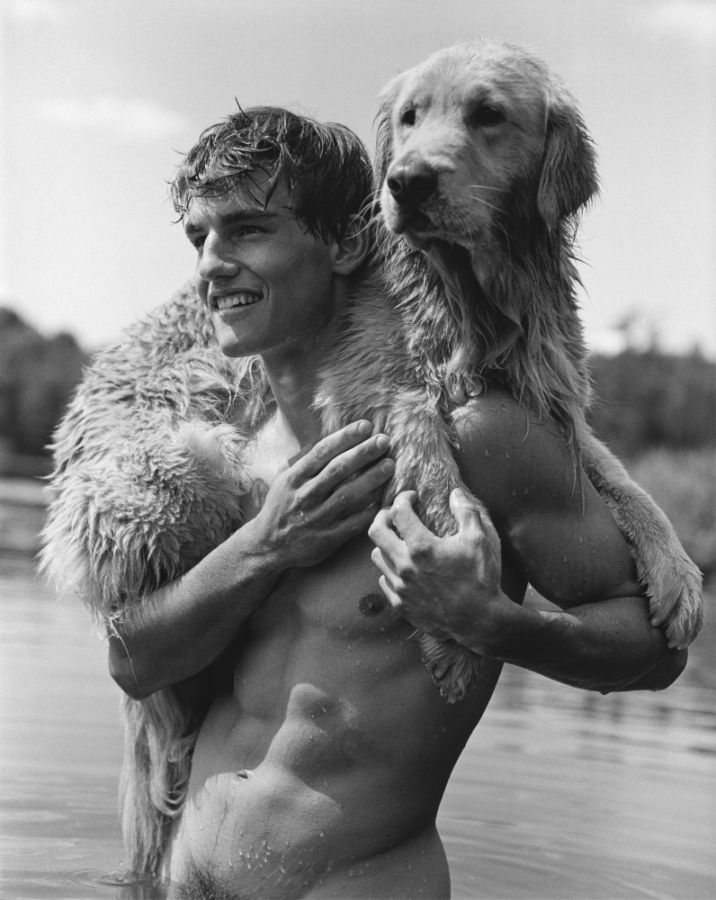

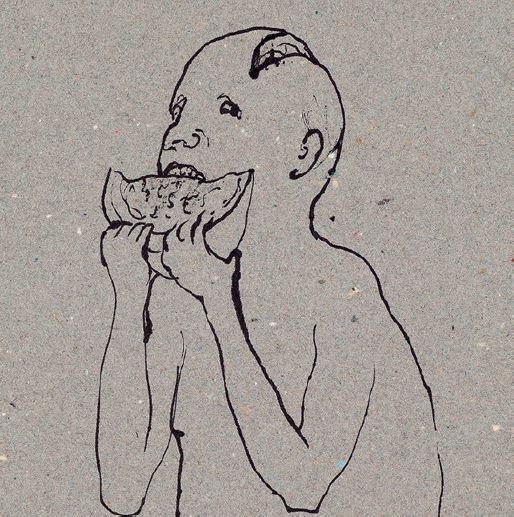

Q. How has your view of the photographed body changed?

TS. I‘ve never focused on looking for beautiful people. I have always been more interested in symmetrical, typical people. The kind of people we would like to send as a message to the universe about men and women, typical representatives of the human race with ideal measurements. That‘s what Leonardo da Vinci, Le Corbusier and I‘m sure many others were concerned with. At the same time, I don‘t believe in absolute beauty. For me, only the partially imperfect or even ugly is beautiful. I hope you can see from the photos, what I mean. When I think of life, it always comes out as cheerful. We‘re born without having done anything for it. We‘re basically born into paradise. The only ones who spoil it are ourselves. If we stay light and creative, we can create so much, it‘s unbelievable. It is necessary to situate one‘s life on the battlefield where one is striving for something.

Q. What is the gist of a victory?

TS. To discover where our uniqueness lies. Not to be afraid of obstacles. When I talk about the battlefield, it‘s probably not an accurate term, since it‘s about being able to connect the different strands. But I see in those who have situated their lives in comfort, that it is difficult and agonising for them to create anything. Anyway, it‘s good to stay away from comfort.

Q. How do you choose your models to shoot?

TS. It‘s not really about selection. Sometimes I want to grant a request for a portrait, but it doesn‘t work out. You can‘t work with everyone, not even the most beautiful models. There has to be a common tuning, a vibe between us, then it totally rings out as a sign that I should do something with this person. It‘s not impossible that this kind of synergy can happen when someone approaches me. But usually, the people I‘m not supposed to take pictures of will want pictures of themselves to be taken. The ones that are cool and good, without any exhibitionism, I have to find myself. So far, I haven‘t had a major rejection.

Q. You say you photograph people who are symmetrical and typical. Václav Havel and František Vláčil were not like that. What attracted you to them? Havel had years of imprisonment written all over his face, Vláčil had his passions…

TS. … and his demons! It‘s about the dramaturgy of my exhibition. It‘s good to include works that go against the exhibition’s prevailing direction. For example, I‘m putting in a large photograph of an extraordinary rag, but still of a rag. It’s ruined, decaying, at the same time it is noble in some way. There is nothing in the photo but the rag and, on top of that, it is a rag at the end of its ragged powers. Alongside all of the photos humming with a restlessness, we need to exhibit images that are calm, perhaps simply coloured, that don‘t make your head think so hard. At the same time, it is about not overloading the exhibition with topics. Not to show all that I have created, but rather to choose the right gradation so that the works are able to communicate.

Q. What do you think about the saying that beauty is in the eye of the beholder?

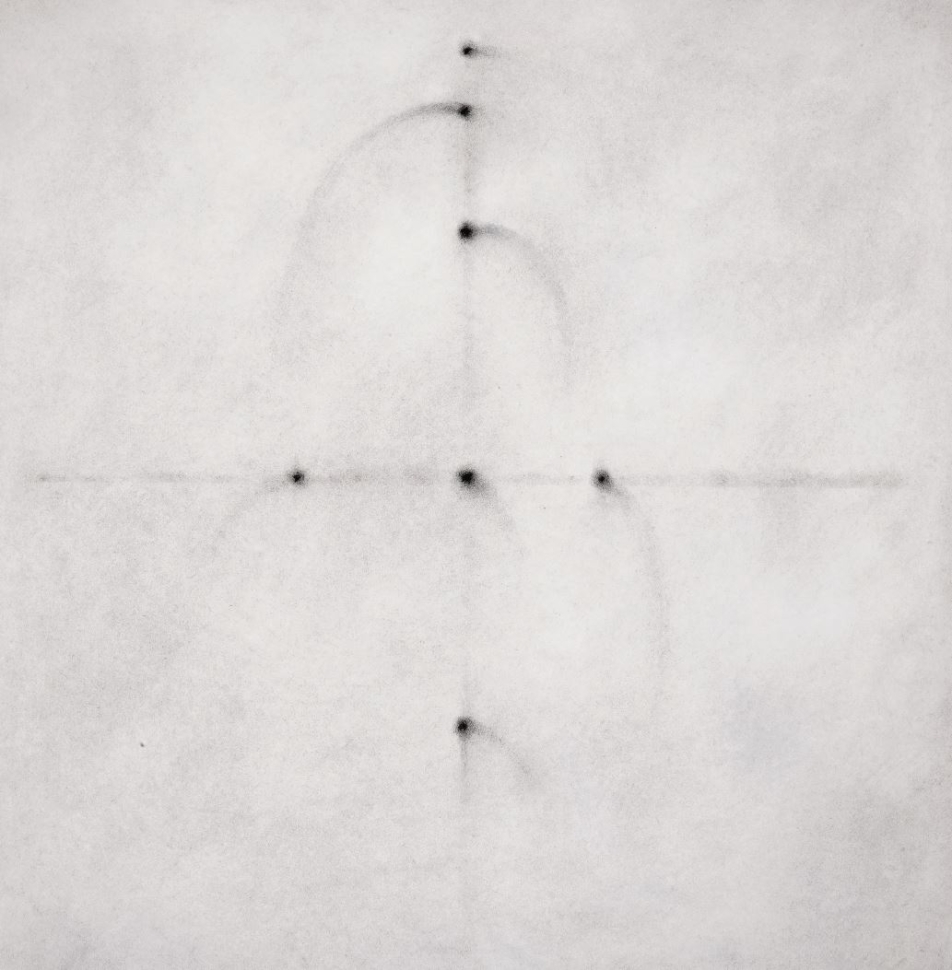

TS. Beauty is very important to me, I‘m not going to make concessions on that. I consider beauty to be an extremely beneficial and important value for life. Of course, there is a certain predilection for ugliness, the cliché that only suffering has meaning. That‘s beyond me, something I don’t understand. At the same time, the reverse is also true. People act on what they themselves find beautiful. My photos, once someone starts looking at them, don‘t quite belong to me anymore. A new situation arises, a fusion of my work with the viewer. The viewers incorporate their experiences into the picture, their knowledge of what they have experienced and what they remember. I don‘t make a claim on what happens between my photos and the viewers. The ideal work, in my opinion, has multiple layers. On the surface, it looks simple but it has a kind of blessing. A good example of such a photo is Sense (1992). It managed to appeal to a very wide range of people, regardless of education, cultural background, or age. Yet, it is a simple image; I suppose ninety percent of the picture is filled with the colour black.

Q. Do you feel part of a creative generation?

TS. Not at all. When I get in the company of my peers, they talk about their age, quite often they feel sorry for themselves and so on. In that sense, I’m in a lot easier situation. One should be born, study and know who one is, what one can contribute to this world. Find that out in the shortest possible time and deal with it. Life is not that long, so I don‘t even have time to think if I belong to some creative generation. My role model is a fruit tree; it also doesn‘t count how fast it grows and how many times it throws out new leaves. It just does what it has to do to produce fruit.

Q. What do you think about time?

TS. It‘s fantastic that you can capture the person you‘re portraying at the right time. There are countless opportunities all around us, and there is just the right time for some of them. The only question is whether we are willing to accept the opportunity. I was born in a village, studied in Bratislava, then I came to Prague to study at FAMU. Bratislava would have been too small for me, I needed a bigger city. I had the opportunity to go abroad, but I wanted to stay in the environment where I belonged. It doesn‘t matter if you work in a beautiful place, where there are many other artists. It doesn‘t matter if you have a studio in New York. What‘s important is to be in an environment, where you can show who you are and what you can do. After the exhibition, I‘d like to move away from the studio, and travel abroad, shooting outdoors. Turkey, Scandinavia, southern Italy, the Balkans and Romania are very appealing to me. I’ve noticed that I haven‘t been to so many places, so I want to indulge myself and see what happens. The time has come.

Q. You say you contribute to society through art. How exactly?

TS. Actually, it‘s already happening. I approached most of the assignments at FAMU as experiments, and I went beyond the instructions I was given. Sometimes I got into trouble, but I couldn‘t help it. It had the effect that very soon people noticed that my stuff was different, and soon after that, I also started to be noticed on the international scene. Selflessly, with no vision of making money, it seemed important to me to create. Eventually, there was an interesting effect. The energy and work, that I put in, started to come back in a pleasantly surprising way, in the form of opportunities, and eventually also money. So if you want to have an interesting life, you need to invest your energy properly. It will come back to you in a positive, if indirect way.