An Ordinary Mug, a Plate and Jitka Svobodová Petr Vizina

The first retrospective exhibition of the artist Jitka Svobodová was prepared by the GHMP for the clean, large space of the Municipal Library’s halls. Her life’s work can be characterised by a few terms – drawing, object, sensibility, quintessence, concentration and time. Each of these sums up a huge number of other messages and possible interpretations. Petr Vizina had a dialogue with the artist in her studio, both about the present and about looking back on her work.

Q We are sitting in the studio where all your works are created. You still live and work in the street where you grew up and went to school. How important is loyalty to place, stabilitas loci, for you?

J S Both continuity and place have always been important to me, for sure. I was born in Vinohrady and I still live here. I wasn’t the type to emigrate; that requires self-assertiveness and I don’t give a damn about that. My artistic generation is practically non-existent, there are maybe three of us who remained here after 1968 and each of us is completely different. Even the work is related to where and how one lives.

Q What does your daily rhythm look like?

J S I used to work long hours; now I don’t have the energy. Good daylight is important for me, so in winter I only work until early afternoon. When it’s dark and you have to turn on the lights, the nuances disappear, the artificial light changes the colours. It would probably work if I was doing something less delicate, but not for what I do. I draw mostly using pastels. They have diffused light; the painting is tangible and its refraction of light is different. Personally, I believe that it is necessary to make one’s way to drawing. It is possible that there are cases of those who draw right from the beginning throughout their lives, but they are exceptions. Either you arrive at drawing or you apply drawing in a different way. Those who go to the academy want to draw. They should go through their painting stage, too. Sculptors, for example, are usually good at drawing. It is the same with me; I painted for eight years and only then did I arrive at drawing. Drawing has an incredible amount of expression. You can draw like Dürer, why not, there were those who drew like that. Or completely spontaneously; it depends on your frame of mind and type. You can make installations, objects, materials and it’s still drawing. My drawing always changes with the subject, as does the way of working.

Q Which theme are you currently working on?

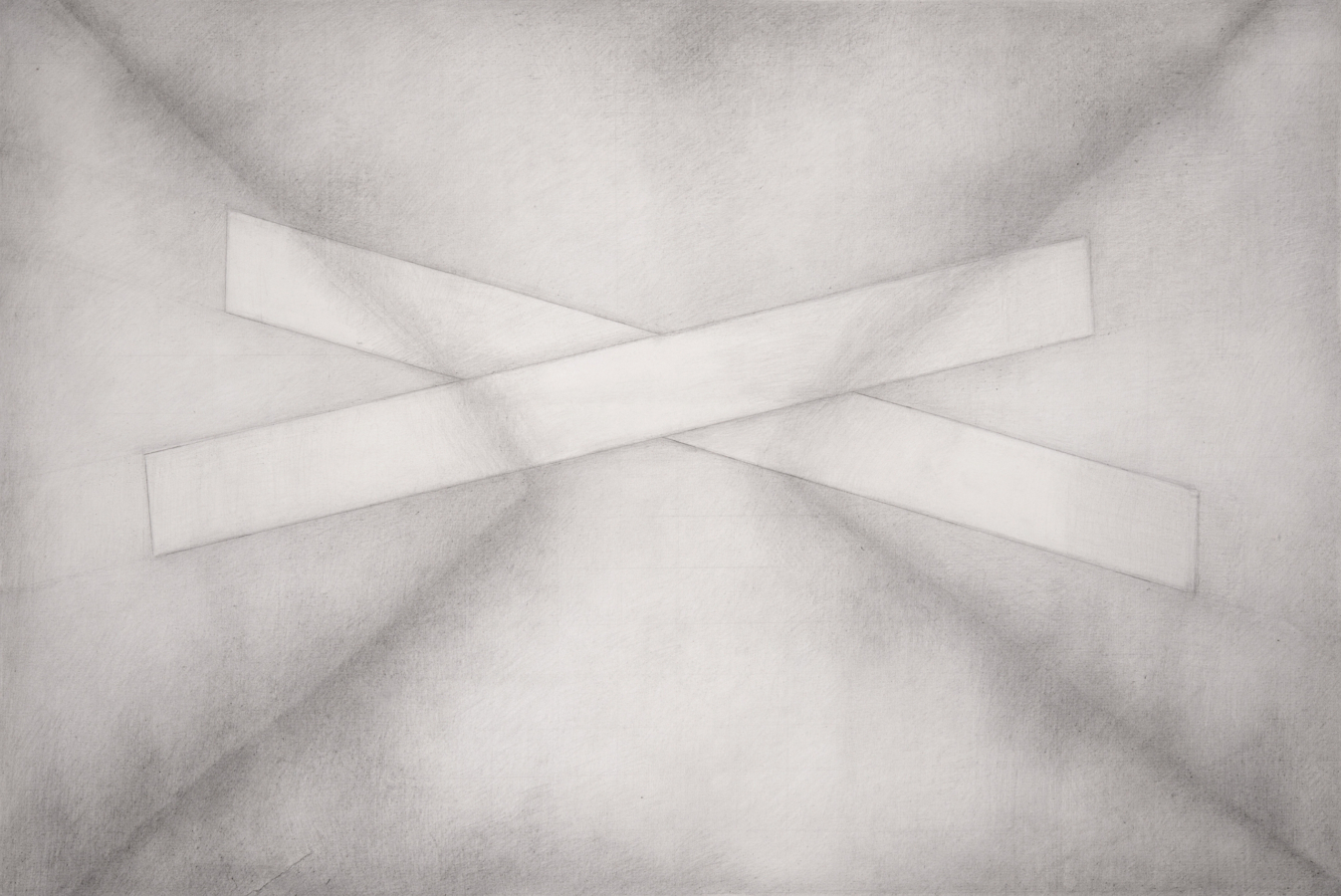

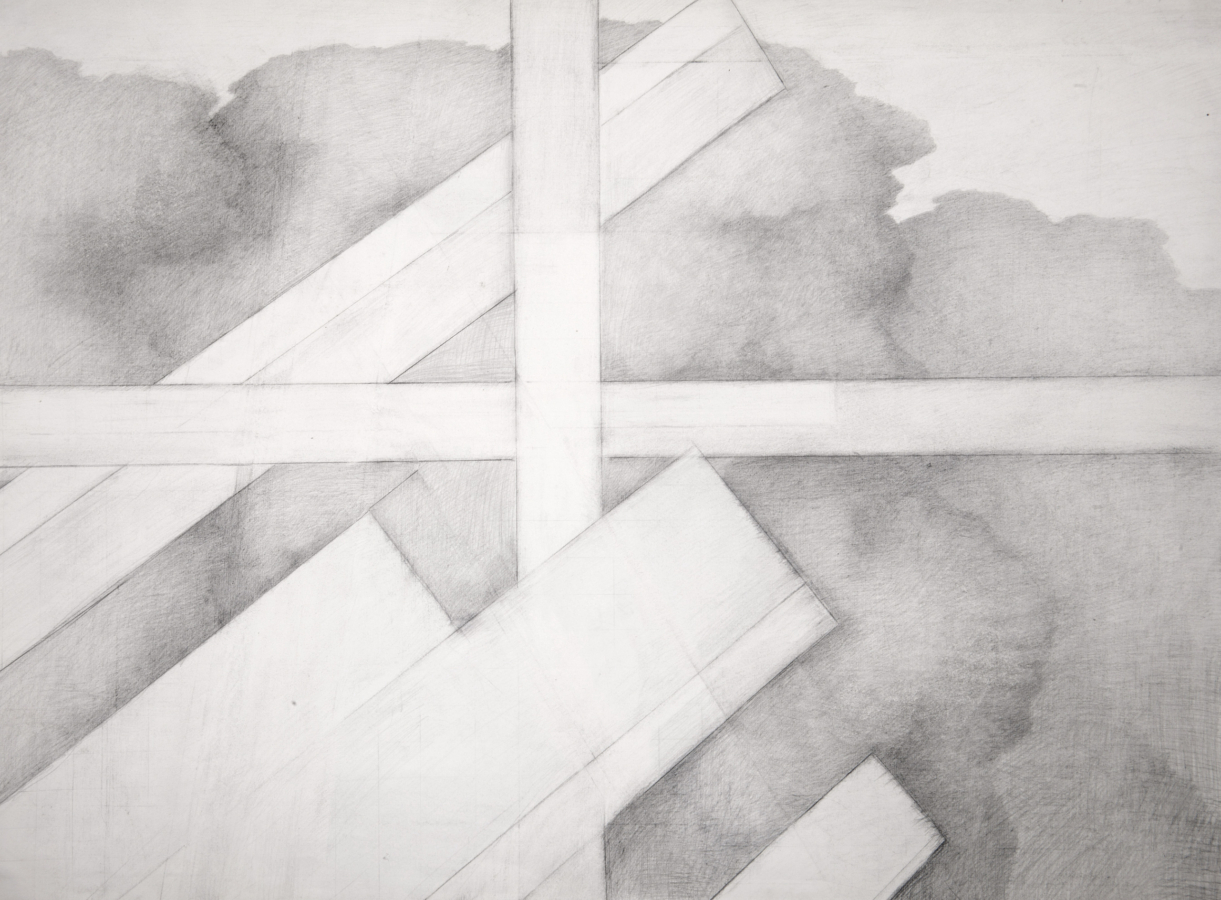

J S I have just finished a big theme, Tablecloths. To a person who doesn’t read the title, Tablecloths may seem to be an abstract affair. However, there is still some content perceivable in the drawings; it is there. I have a lot of my mother’s tablecloths at home, traditional ones, beautifully decorated, but I try to deny the visual aspect. Today’s world is very visual; the Internet, television and advertising attack us. With each of my themes, I want to continue to be more reductive. The important thing is that the drawing is made by hand. That’s why I’ve never been interested in graphic art because it works with printmaking, but what I need is the touch of the hand. Printmaking will create amazing things, but that’s not what I’m after. I want to get to a certain essence of the thing.

Q How did you manage to achieve this with the tablecloths?

J S I realised that a tablecloth is actually almost always a rectangle or a square. When you unfold it and put it on the table, it’s just that rectangle or square again. Originally, I was just taking the outlines as a basis, but then, with the larger rectangular drawings, 170 by 135 centimetres, it occurred to me that when you fold the tablecloth and then unfold it, there is a kind of grid on the tablecloth. So I drew the grid of the folded tablecloth in the rectangle, but unfortunately, I can’t think of any more variations. That’s the end of the tablecloth theme for me.

Q Does the larger drawing of the three round tables that you have leaning against the wall here belong to the theme of tablecloths?

J S I tried to draw the covered tables, as you can see in the painting on the wall, but it’s too visual a theme for me. It’s more for relaxation. You see, I don’t work towards a big reduction all the time, sometimes I do something more realistic. But then again, I have a huge urge to get something into that minimal position. I’m fascinated, for example, by the fact that a mug or a plate are almost unchanging forms. I mean, designers come up with all sorts of things, but that’s bullshit. A plain mug and plate are the essentials. I was most fascinated by their interior space. Strangely enough, even when things are static, they usually don’t have anything static about them. I tilt them. Because that’s what I feel I should do. The surface I’m drawing on itself is static and passive, which is why, for example, I shift the mug I draw several times a day. Or I tilt it a little bit. But it can’t be too much, just a little. I’m not concerned with perspective at all, I’m interested in subject and space. When you look into a mug, it has an inner space. I would also mention the themes of Pillows, Tables and Curtains in terms of my current work; before that, my big theme was Eyes. The sign of a great theme for me is when I can work on it longer and it keeps opening up. But sometimes I just do a few things and that’s it.

Q What theme did you fail to “open”?

J S Smoke was an amazingly big topic that I haven’t been able to fully revise. I used to take the train to Ústí nad Labem, and we would pass chimneys that smoked amazingly. Not that that was the inspiration, but smoke has a certain dynamic. In a drawing, however, the smoke came out too static. I realised it would be good to film it, for example. In a film, smoke would definitely be more interesting, but I don’t want to venture into other media, even though it’s fashionable nowadays. I’d have to delve into it a lot, not just film the smoke. I can’t do anything straight off.

Q How do you actually choose your themes – tablecloth, pillow or smoke?

J S It’s always good when the stimulus comes from the outside. The impulse means that something speaks to me and I have to approach it somehow. I need to rethink that impulse. Sometimes it works, sometimes less so. Sometimes it surprises me, at other times I am unable to do anything with the subject. But it always comes from a certain impulse from the outside. It’s a chance occurrence that has to come from above. Of course, you can come up with themes, but that doesn’t quite work for me. Of course, then I think about it and keep inventing. Then I think about the task. Either the theme goes away or it doesn’t.

Q You actually came to the seemingly simple themes of your drawings involuntarily, under the existential pressure of normalisation in the early 1970s. Was that so?

J S I studied painting at the Academy and was constantly creating. But my mother, who spoke three languages and worked in foreign trade, was fired at that time for political reasons and my father had a heart attack. I realised that I had to look at the situation realistically and I had to be able to earn a living. It’s not possible to stay with your parents and have the advantage of having a place to live and something to eat. I decided to go on to study painting restoration. It was a good technology lesson, and it helped me in my own work. I can fix a painting or a drawing. I took it purely as a source of income, but you have to enjoy the work at the same time, it is extremely demanding of time and patience. We mostly worked on ceilings that nobody wanted to do, under terrible conditions. It was ten below zero, there were no doors or windows, we were plugging the holes with plastic, it was freezing, but the work had to be done. The water mains were wrapped in sacking, we carried buckets of water that splashed into our boots. I didn’t have time to paint anymore. I thought I was done with art. In that moment of personal crisis, drawing came to me of itself. I told myself I would make little records of my surroundings. I drew the planks I walked on, the scaffolding, the wires, the light bulb, the ladder. Until then, I had been focused on painting, abstract landscapes, for example. Suddenly, I was drawn to the very ordinary things that surrounded me. From that, the enormous simplicity of the world in which I was operating developed. At that moment, I understood that simplicity suited me. There was a kind of socialist realism in vogue at the time and so my path was a solitary one. Jiří Kolář bought me something, but that was about it. Jindřich Chalupecký didn’t reject me but he said that he preferred female artists who worked with their own bodies. Eva Kmentová, for example, imprinted herself in plaster, Adriena Šimotová also thematised femininity, but I was never good at it. I was a freelance artist until I was almost fifty, before I got to work at an art school, thanks to Knížák. He invented a drawing school. Drawing had never existed as a separate discipline, there was only a preparatory course at art school that everyone took in the first two years of study.

Q At the time when you were only drawing after work, who were you able to talk to about your work?

J S If anyone’s opinions on my work were really important, they was probably Adriena Šimotová’s. I assisted her for a few years, and it was very important for me because at that time, I was studying restoration and I was using art to relax. Adriena was surrounded by famous artists, so I was able to get a glimpse of them. Otherwise, I don’t discuss anything with anyone concerning my work. You see, I’ve found that when someone gives me advice, it doesn’t really affect me. Another question is, why doesn’t it? Sure, it’s good to have someone give you their opinion on what you’re doing, but I don’t think you should always accommodate it.

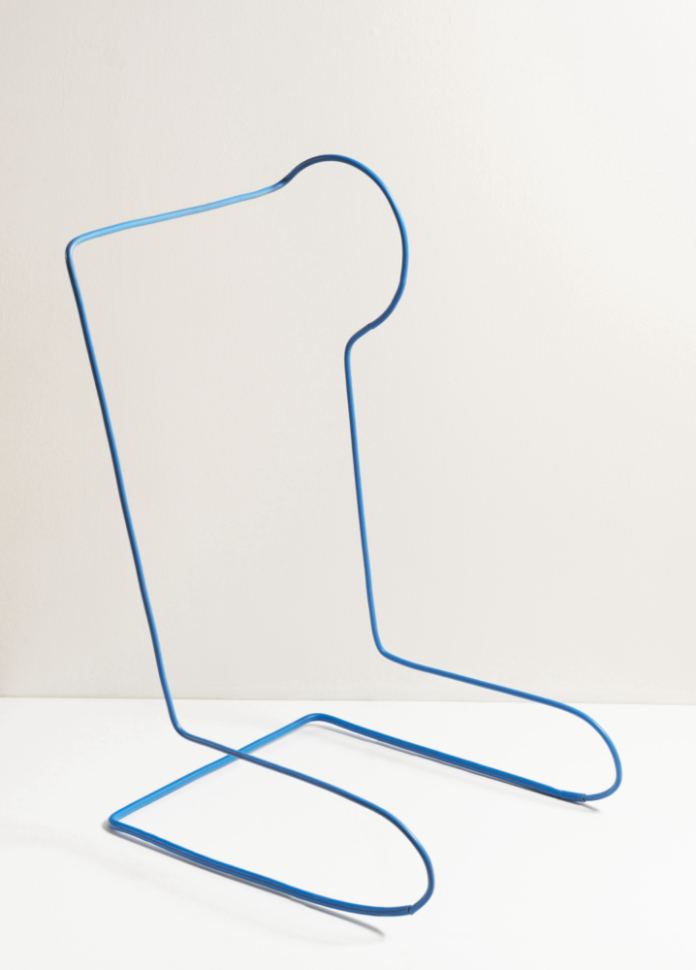

Q In your studio, you have wire objects – both small and large. Are they related to the drawings?

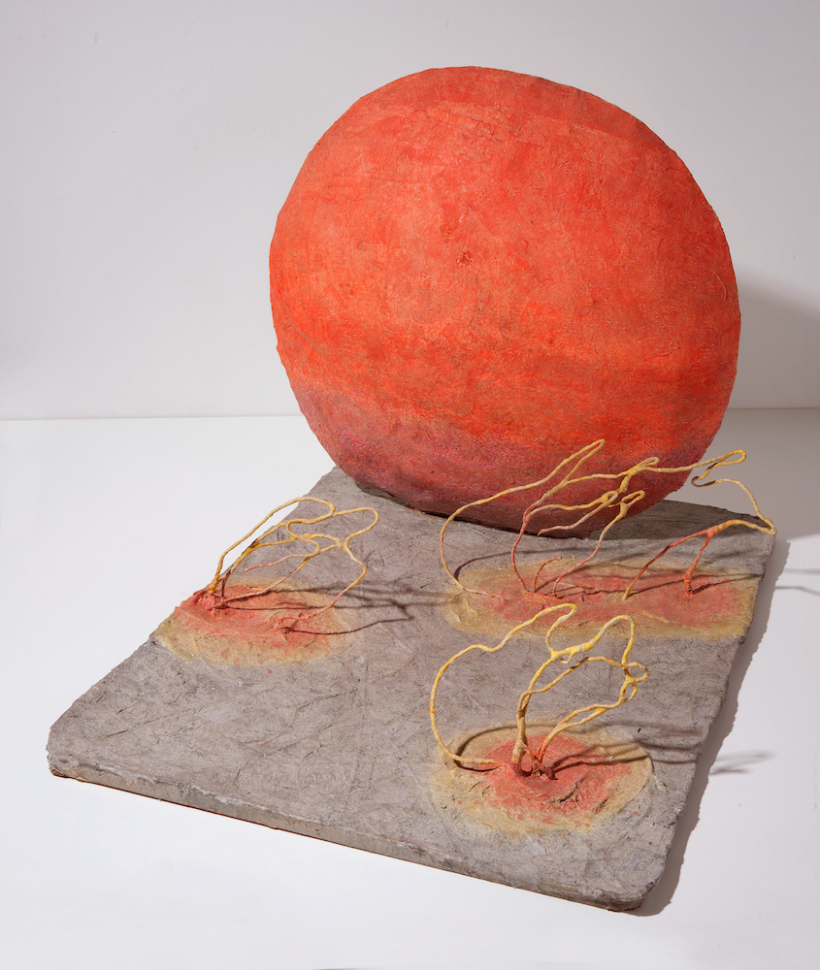

J S The wire objects are mostly responses to my drawings. When I was drawing vessels, cups and plates, the wire was good for creating their outlines. You can make it all big, too, but then you need someone to weld it for you. Or, for example, I used to do the Fires on my own. I thought drawing fires was silly, I tried it, but it’s kind of bland. But in wire, it had tremendous dynamics. When you go around it, it changes and you really get a sense of fire. I’ve always been attracted to wire as a material. It reminds me of drawing, I’ve always been fascinated by the fact that you bend the wire and it’s there, whereas drawing it… Plus, wires have coloured insulation nowadays. Mostly, I just work with used materials. They have a certain patina, plus the used wires aren’t exactly straight. They have their own sensitivity. I’m making spiders now. They’re neither drawn nor made out of wire, but from bonded wool. Most of my works are static, the spiders move. There are plenty of spiders. I don’t know what happened; I have spiders in my bathroom and in my kitchen. There’s also a big increase in the number of spiders in Senohraby, where I go to. I enjoy making spiders but I’m afraid there’s nothing more I can do with them.

Q Trees are a constant theme for you. Do you consider them as static or do they move?

J S Trees are not static; a tree moves. A tree is like a person, each one is completely different, each one grows differently, askew, in all sorts of ways. Unless someone destroys it, it’s like a human being, it lives a long time. When a tree sheds its leaves, it’s completely different, like a human skeleton. It’s strange. Actually, I don’t know why I make trees. They’re really an ongoing theme for me. I’d like to start my exhibition with trees because, strangely enough, I come back to trees regularly.

Q Which quality is most important to you, patience?

J S Patience? I guess so. I don’t care if something doesn’t work out, I just keep trying.