Although life is gradually getting back to normal as summer approaches, plans for the future remain unclear, especially for culture. An Uncertain Season is thus not only a reflection of feelings shared across society, but also an illustration of the state of the Czech art scene. In a time that does not provide a solid base for the creation of new work, the way to find certainty seems to be to reflect on what has been done so far. Fortunately, gallery collections provide such inspiration. The exhibition at the Troja Château offers works by Karel Malich, Stanislav Kolíbal and Hana Wichterlová, and does not overlook artists of the younger generation, such as Matěj Smetana or Pavla Sceranková. The interpretation of the theme is as diverse as the representation of Czech artists is wide – while for some, a robust industrial building may simultaneously symbolise both threat and stability, others seek peace and grounding in natural phenomena and laws. Four of the artists talk in more detail about what the works on display mean to them and, ultimately, what role uncertainty plays in their work: Jitka Svobodová, Jaroslav Róna, Pavla Sceranková and Petr Lysáček.

The Elusiveness of Phenomena

Jitka Svobodová

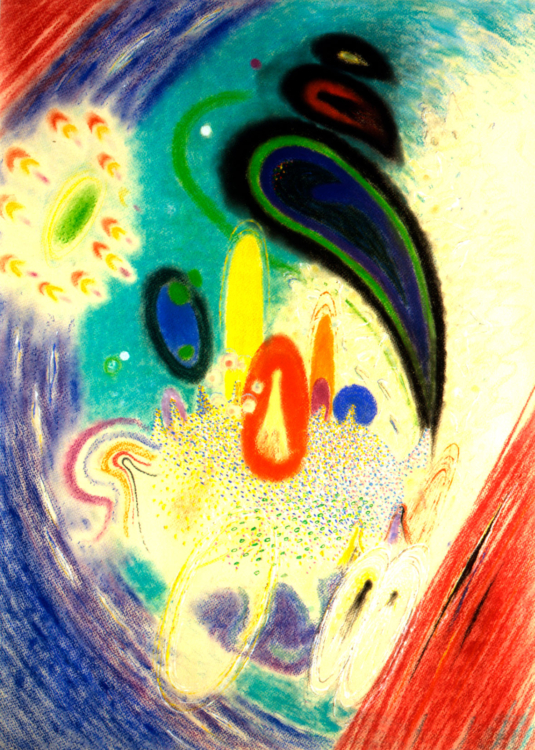

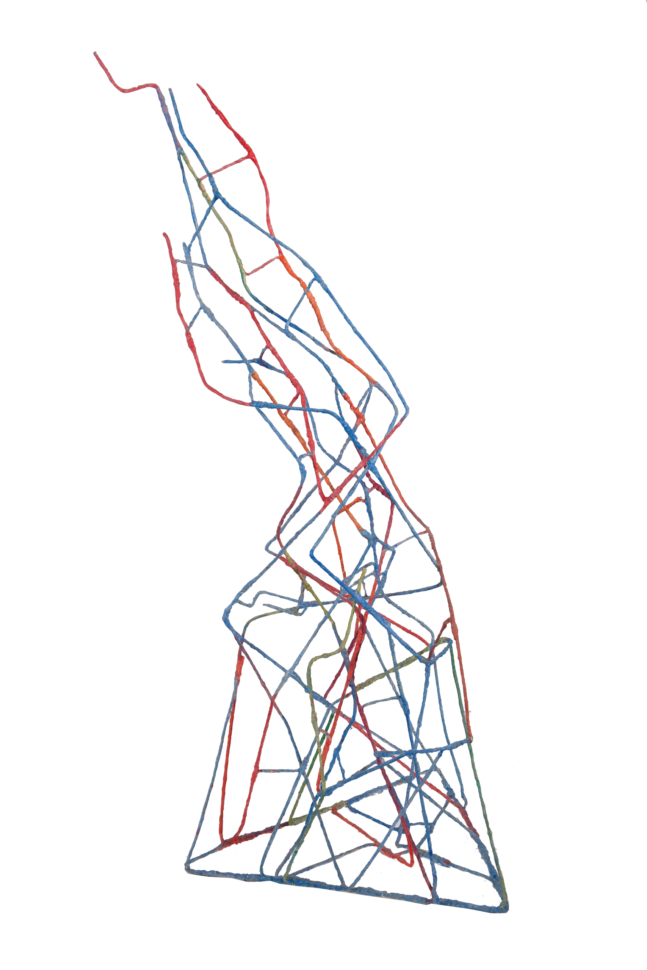

Natural phenomena fascinate me. Fire is stunning, but artistically very complicated. I couldn’t find a form for it in drawing; it always remained conventional. An object made of wire, on the other hand, gave me an amazing opportunity: you walk around it and the broken wires draw, mutually interconnect, and give the fire its own dynamics. But I’m not looking for any symbol in it. I’m working with tangible matter and trying to bring it to a different level than the real, to the edge of visual and rethought abstraction. At the moment, I’m working with pastels and I’m totally immersed in the shades of colour. Wire, on the other hand, is a drawing. You can look for a shape and dynamics with it; it won’t allow you anything else. These techniques are absolutely different, but working with one of them gives me a break from the other one. What captivates me about natural phenomena is their ephemerality, their elusiveness. I used to be very fond of smoke. I devoted myself to it for a long time, but I didn’t really get anywhere with drawing it. If I were to make smoke or sunlight even more abstract, they would be unrecognisable. I’m constantly focused on a phenomenon being a phenomenon, but in a new light.

I feel challenged to depict basic natural elements such as fire and water. Even though I know it’s very difficult. But each thing opens up a bit of the future, of course. There’s a lesson in it, an experience. You don’t have to consciously apply it, and yet the work slowly goes somewhere. When I started studying restoration, I didn’t have time for anything else and thought I was done with making art. But everything came back. In the evenings, I had the desire to create, and started with small records of everyday things. This is how, eventually, my drawings came about. They emerged automatically. An artist needs to have an energy inside that forces them to work. But they should also be insecure. Making art means change; you can’t just produce art mechanically. But a certain uncertainty makes you think about things all the time.

Deterrent Fortification

Jaroslav Róna

The Church is a sculpture that looks somewhat absurd, like a fantasy building, but its shape is based on history. Many monasteries and churches functioned simultaneously as fortresses or fortified residences, protecting the inhabitants and monks against invaders, especially in the period after the fall of the Roman Empire. The combination of spiritual ministry and military deterrence appeals to me. There is a water tank on the roof and the perimeter of the church is flanked by narrow horizontal embrasures. The basic shape of the building I completed is based on a found object that came to me in a complicated way and originally served as an element in the production of light aircraft.

Cities, especially their industrial districts, have always been a source of danger and a target for enemy attacks. I grew up relatively close to the end of the World War II, and later, during the Cold War, I strongly felt the threat of bombs and missiles. Perhaps that’s why I use fortresses, bomb depots, missiles and

the like as subjects for my sculptures. My artistic intuition led me to return to these war motifs. I also visit fortresses and fortress towns frequently when travelling – for example Masada and Akkon in Israel, Valletta in Malta, Rhodes in Greece and Syracuse in Sicily.

On the one hand, artistic work is a way of personal realisation that brings joy, on the other, it represents a response to the everchanging reality in which the artist lives. The impulse to create art can thus be both the joy of life and a sense of threat and instability. But uncertainty can never be contained. Of course, I do not live paralysed by fear of World War III, but I do not underestimate the current threats, for example, from Russia. I see a symbol of stability in a militarily strong grouping of democratic states that can deter potential aggressors. However, I think that the period in which I spent most of my life was

much more uncertain than the present time.