Antonín’s photographs capture scenes from local, European, and world history and conflicts. His images from Central and Eastern Europe in the 1980s and ’90s, which offer a unique and comprehensive photographic overview of this region, were published in his first book, Broken Dream: 20 Years of War in Eastern Europe (1997). They reflect Antonín’s subtle sense of nostalgia and the scars that opened up when he, as an émigré with an American passport, began making repeated visits to his original home after 1976. Above all, however, these visits produced an indelible photographic record of the atmosphere of and life in the neighboring communist states. His images from Poland, East Germany, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and the Soviet Union are dominated by two subjects: the impact of industrialization on the landscape and life in the poverty-stricken, forgotten countryside. Antonín was strongly attracted to the question of people’s roots, moral codices, religious ceremonies, weddings, and funerals, and so he explored and documented in depth the rituals that people had maintained despite poverty and communism – in Poland, Hungary, and especially Romania. These places never lost that munificence of humanity and the sense of pride one feels from being a part of it.

Another of Kratochvíl’s grand themes is the question of endangered children. In Mongolia, Guatemala, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Pakistan, the urban labyrinth of sewers belongs to gangs of children. Abandoned and orphaned, left to fend for themselves on the streets, they easily fall into the machinery of crime and brutality. Hunger, drugs, money, prostitution, prison, and death are the specters of the uncontrollable roulette of their lives, often with no possibility for change. In 1988, Antonín’s photographs of this immense problem made as part of a reportage about children in Mongolia earned him the prestigious Alfred Eisenstaedt Award.

Antonín’s photographic adrenalin has also offered us insight into some of the world’s worst prisons. In 1997, he photographed Venezuela’s El Dorado prison, which is ruled by drug gangs and gold. Ten years later, he visited an unguarded prison in Guinea-Bissau from which there is no escape, and in 2002 he took a famous photograph from a prison in Myanmar located at the center of the opium triangle on the border between Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand. This picture showing dozens of drug dealers sitting cross-legged in wooden cages won first place in the most prestigious category, General News, at the 2003 World Press Photo competition.

War represents the escalation of human conflicts. Antonín Kratochvíl has documented numerous modern wars and genocides in Rwanda/Zaire, Guatemala, Congo, Haiti, the Philippines, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, and the former Yugoslavia. His records of reality are a source of information on and direct witness of the current state of civilization. The desacralization of all areas of human existence has taken on genocidal dimensions, leaving behind a trail of death, slavery, environmental devastation, and subverted and deformed moral principles and values.

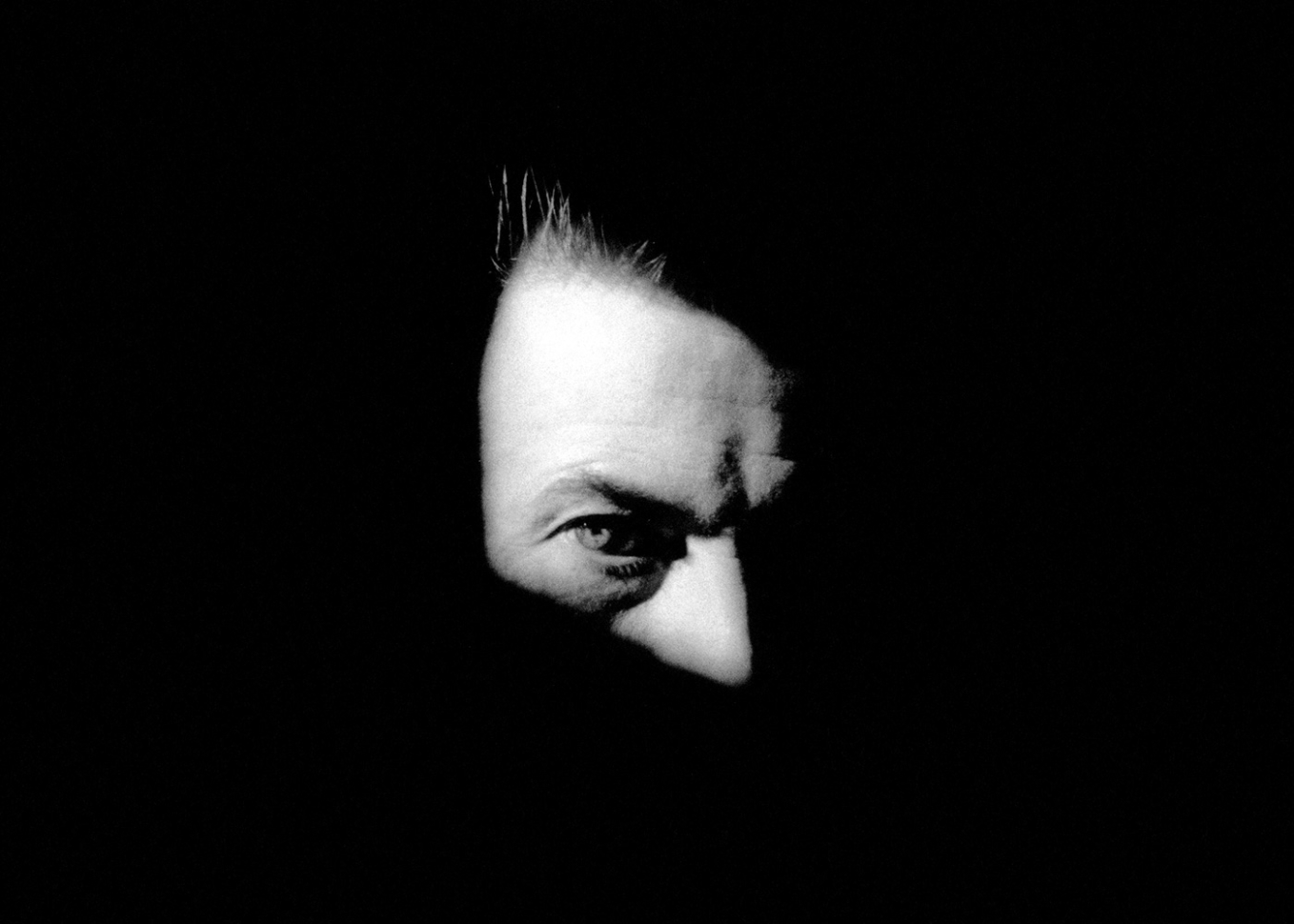

What, then, is the outlook for the future? We will probably have to dream up a new, different, better world. This change can be realized once we are sure about what we want and how we want it. For now, we can find inspiration in the last section of Antonín Kratochvíl’s exhibition, which looks at human dreams, hopes, and prospects. Come and see how the stars are turning! By mixing portraits of completely unknown and anonymous people with photographs of celebrities such as Jean Reno, David Bowie, Billy Bob Thornton, Willem Dafoe, Debbie Harry, Patricia Arquette, Amanda Lear, Mejla Hlavsa, and Pavel Landovský, the exhibition offers an allegorical celebration of humankind. Antonín captures their state of mind: His photography is his way of understanding people, his non-verbal witness of empathy and the relative nature of beauty, fame, and success.