Drawing and Construction or How Film Learned to Build Michal Bregant

In Czech and world cinematography, the period 1918-1945 is a very rich and very long one, as it involves fundamental changes in style and narrative as well as in technique and technology. These are all communicating vessels. In order to understand these changes today, it is useful to imagine how audiences, their experiences and their expectations were changing over three decades.

The same can be said of theatre audiences or visitors to art exhibitions but I think that the developments in the field of cinematography was particularly revolutionary. It is not just the breakthrough in terms of sound, which occurred in our country around the middle of the above-mentioned period but perhaps even more fundamental were the social and aesthetic changes. Karel Teige and his generational contemporaries were strongly critical of contemporary mediocre films and admired the beauty and authenticity of early turn-of-thecentury films and the poetics and adventure of American slapsticks and western movies. The avant-garde did not despise the realistic mode of representation but rather the stereotypical affirmation of conservative bourgeois values.

The concept of realism had very fluid contours in film discourse since the invention of the cinematograph. The ambition of filmmakers was first to tell a dramatic and emotionally stirring story, often based on literary texts. Gradually, film makers learned to portray the natures of film characters, and a major role in this process was played by technical advances in the recording and reproduction of sound synchronous with the image. When silent films in the cinema were accompanied by music or other sounds to complement the action on the screen, there was no shortage of emotion. However, this was mostly for illustration, at best an extension of the narrative field of the story. Once the characters began to speak on the screen, their psychological potential intensified, their motivations seemed more convincing.

Does this mean that sound films were more realistic than silent ones? No, they were just more similar to the way living people communicate, while at the same time stripping that communication of the magic of compression and uncertainty that films used to have before the advent of sound. Film was now able to portray the environment, characters, and conflicts more faithfully to what audiences were used to from lived experience.

The New Realisms exhibition does not confront realist perspectives directly with other ones but there is at least a virtual presence of both the view of the Devětsil avant-garde and, for example, state-forming representation in art and culture. In terms of style, the confrontation in the field of film and cinematography would need a large space for visitors and viewers to appreciate the differences in time and meaning of each work. For example, Otakar Vávra, represented in the exhibition by his experimental debut The Light Penetrates the Dark (together with František Pilát), developed his talent in the period under discussion by imitating various styles, ranging from civilian dramas to historical epic feature films, always with the intention of representing the political

context of the time, including the style typical of Karel Čapek. Alexander Hackenschmied, on the other hand, was able to use the medium of film as a tool of mobilisaton in a moment of danger, when he made his documentary The Crisis in 1938 which dealt with the cultivated coexistence of democratically oriented Czechs and Germans and contrasted it with the manipulated German citizens of the Sudetenland.

Films that construct reality rather than portray it But back to the films in the exhibition: what unites them is their ability to construct a new reality, that is, to use the immanent expressive means of the cinematograph apparatus to break down the descriptive framework. Of course, it could be argued that descriptive realism is also a type of construction, i.e. the attempt to make the world on the screen resemble lived life, to mirror it faithfully. But what does construction mean in relation to „portrayal“ in creative practice? Neither the attention of the artists nor that of the audience is limited to judging the fidelity or infidelity in the representation of reality as it appears to the camera lens or the person who controls it; instead, attention is demanded by unexpected visual attractions, such as close-ups that call for a revelation of meaning, angles of view not usually available to the human eye, proportions that surprise. Such attractions only gain significance through confrontation, through unexpected

compositional arrangements that require a new type of activity from the audience: the identification and interpretation of meanings. Such a construction of a new reality is not the prerogative of avant-garde determination but a symptom of the open modernist cultivation that not only Czech and Czechoslovak culture underwent between the end of WWI and the end of WWII. This is why we also witness the penetration of avant-garde stylistic practices into the mainstream, commercially oriented production in our cinematography in the interwar period. The fusion of the experimental and the mainstream, which then occurred many times during the twentieth century, was the basis for the construction of a specific reality of this medium in the sphere

of film, a reality that cannot be captured and expressed by any other means than the dynamics of audiovisual tools.

How to exhibit films It is one of the good traditions of the GHMP that it tries to integrate different kinds of art in its exhibitions. When Helena Musilová approached us to participate in New Realisms, only a few weeks remained until the opening of the exhibition. There was no time for a new solution to the problem of „how to exhibit film“, so we took the usual route. The exhibition features one film on a separate monitor, one short film in its own cubicle, and five short films, representing both the diversity of contemporary approaches and the diversity of the film portion of the Národní filmový archiv, Prague entire collection, screened in a black box. I find Alexander Hackenschmied‘s eightminute Aimless Walk to be an extraordinarily intense work that in itself represents both the poetic and social-realist perspective of its time. Across Prague in the Spring of 1934 exemplifies a socially critical perspective that seeks to analyse visually and, most importantly, in terms of composition.

For the aforementioned The Light Penetrates the Dark, it would have been ideal if a reconstruction of Pešánek‘s lightkinetic sculpture, created on a smaller scale by Federico Diaz for Pešánek‘s monographic exhibition at the National Gallery in 1997, had been on view somewhere near. Pešánek‘s original work was a direct inspiration to Vávra, and its luminous effect is at least partially captured in the film.

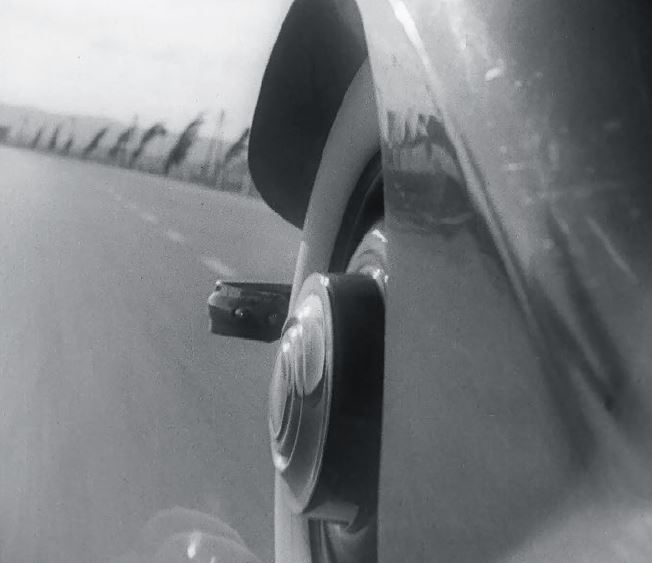

The other two films represent the theme of technology, commerce and advertising as social facts of their time. How We Make Posters, which was shot under amateur conditions, relates not only to production technology but also to the importance of the poster as a communication medium in its time. The Highway Sings was made as an advertisement for Bata tyres and is traditionally presented in the context of avant-garde tendencies in our film. This is due to the refined visual and compositional quality, again with Alexander Hackenschmied playing a major role.

The Hands on Tuesday, a short experimental film by Čeňek Zahradníček, is on view as a stand-alone work in the part of the exhibition where the theme of human hands dominates. The inclusion of this film may have been a little premature, as the Národní filmový archiv, Prague is only now embarking on its reconstruction and restoration thanks to the discovery of other versions of this work, but it

still plays a significant role in terms of thematic connection in a particular context, which may perhaps bring some surprises to the visitors.New Realisms is in many ways a groundbreaking exhibition. Personally, I am extremely pleased not only with the conceptual innovation of the „Czechness“ of the artists and their works on display and their return to the public sphere, but also with the natural integration of media other than painting and sculpture. Without photography, printed periodicals and films, the account of the cultural activity in Czechoslovakia at the time would not be as convincing. It would certainly be possible to expand the scope of the exhibition to include radio and other social or cultural phenomena, but that would be another exhibition.

The trailer for Gustav Machatý‘s film From Saturday to Sunday was created by Jan Bušta and his collaborators. This opportunity came about thanks to the digital restoration of the film that we undertook in 2016. Jan Bušta is one of the artists who are approached by the creators and producers of contemporary films to create trailers and other teasers for them. With his trailer, Bušta not only serves Gustav Machatý‘s work, but updates, reframes and interprets it in terms of image, sound and composition. His trailer is an audiovisual work of its own – which is why its presence in the

exhibition was Helena Musilová’s explicit wish.Machatý‘s film itself remarkably pushes forward the traditional sentimental narrative of a chaste girl who almost gets hurt but, after the misunderstanding is cleared up, all ends well. As in Erotikon and Ecstasy, Machatý interprets the essentially banal plot, borrowed from pulp literature, with a bold, innovative language that places him in the circle of New Objectivity or New Realism. That is why we screened this film in April at the Ponrepo cinema, where we followed it up with three more evenings: the socially critical drama Such Is Life directed by Carl Junghans was followed by a selection from the non-feature-film part of our collection (three documentaries and one news film) and finally Otakar Vávra‘s Virginity. We consider the screenings at Ponrepo to be an integral part

of the exhibition, and we hope that visitors will continue to find their way to the nearby Ponrepo cinema in Bartolomějská Street, which offers a unique programme of classic films of

all types, genres and provenances, and is thus a kind of permanent, but renewed exhibition of Czech and world cinematography.

Tarantula is Missing in the Exhibition The selection of films from the collection of the Národní filmový archiv, Prague for the New Realisms exhibition could have been much broader. It could include not only newsreels or other documentaries but also animated films that in the 1930s struggled with the requirement of faithful representation of the human figure and characters. (Although that would probably get us literally to the portraying I mentioned above in a figurative sense.) Personally, I miss Tarantula in the exhibition – a short documentary with a period-specific educational or awareness-raising ambition. However, another monitor did not physically fit into the part of the exhibition that treats the subject of native plants, especially cacti. The visitors can view Tarantula by clicking on the link bellow, at least on the Národní filmový archiv, Prague YouTube channel.

Michal Bregant is the CEO of the Národní filmový archiv, Prague and President of ACE – Association des Cinémathèques Européennes; his professional interest is history/ies of cinema and culture