I Don’t Think There is a Clear Definition of Where the Boundaries of Photography Are Klára Fleyberková, Pavel Klusák

What can we learn about the potential, forms and impacts of photography in our postmedia era? What is its role since being adopted by the Internet and social networks Jitka Hlaváčková invited ten curators to participate in the Divination from a Night Sky Partially Obscured by Clouds exhibition. They brought artists and works to the exhibition. “Through responses from a dozen theorists, we offer a fragmentary probe into postmedia photographic and digital imagery that at least symbolically captures the hybrid and highly networked nature of our situation,” writes Jitka Hlaváčková. The specific nodal points in the network are presented in interviews with four of the participating artists: they are Alena Kotzmannová, Alexandra Vajd, Markéta Othová and Ivars Gravlejs.

Alena Kotzmannová

Apparatuses of ImaginationQ A series of your works from 2019 flies through the exhibition at the House of Photography like a meteorite. How was Oumuamua actually created back then?

A K I have long been interested in space research and space-related topics. I enjoy exploring something that transcends us and that we don’t fully understand. The news that a body entered the solar system that astronomers had never encountered before immediately intrigued me. Oumuamua means “messenger from the ancient past” in Hawaiian. It turns out that the object must have been travelling through space for some time before it entered the solar system. And once it was here, it disappeared again. There was no way of capturing it, photographing it, so subsequently various visualizations began to emerge that resembled an elongated, cigar-shaped stone. I’ve been interested in stones for a long time, fascinated by the fact that they have been here much longer than mankind. The messenger Oumuamua simply fitted into my thinking and I decided to create a fictional account of its visit to our solar system.

Q You chose the scanning technique. Why precisely this one?

A K Because I know its limitations. For example, I can never achieve a white background by scanning an object. That’s what I thought of when I thought of the night sky. In addition, I thought the dirt particles on the glass might well evoke stardust. Also, due to the passing light beam, the object doesn’t cast a single shadow, it’s not brightly lit from one side, so the whole space around it is kind of elusive. Related to this is the possibility to completely avoid an input of a human with a camera into the whole process. Me, a human being who would capture and document the phenomenon, is missing because that’s what’s never really happened in the case of Oumuamu either. Looking at the installation, the visitor is puzzled. Just like people think they understand photography, they also think they understand the universe quite well; but then an unknown body flies in and shifts the whole idea somewhere else.

Q So you enjoy pushing the boundaries of photographic representation?

A K I don’t think there is a clear definition of where the boundaries of photography are. For me, it’s always a combination of intuition, different types of thinking, and choice of camera. Any kind of camera. The evolution of photography has been rapid since its invention. I’m comfortable being open to whatever comes along. Even when I was studying, when I was still taking pictures using a film, I liked to experiment with the possibilities of the medium; and that was long before digital post-production was even considered, which adds more possibilities for creative approaches.

Q You will now be teaching the next generation of photographers at UMPRUM. How much will you guide them towards the technical roots of photography?

A K When students master the basic technical skills, they open the door to other creative layers. They don’t shoot from the hip. And I’m actually surprised at how open the current generation is to using analogue techniques, shooting while using rolls of film, adventuring with camera obscura and so on. It’s the same as with history in general, it’s always repeating itself in circles somehow, going back. I also use different kinds of cameras interchangeably and the fact that it can be blended suits me. For example, it’s common for me nowadays to have a kind of bizarre combination of scanned negatives that I print digitally. Why not? Anything is possible, but it only makes deeper sense to me if we don’t prioritize the technical nature of the cameras, and instead what remains primarily are theapparatuses of imagination.

Q This is actually what the exhibition at the GHMP shows.

A K In my opinion, the exhibition suggests that imagination is not just an abstraction of the pressing issues of the contemporary world, but instead can be a concrete way of naming aspects that are otherwise difficult to realize or acknowledge. Divination from a night sky partially obscured by clouds aptly speaks about the elusiveness of the medium’s boundaries. Similarly ungraspable as Oumuamua.

Aleksandra Vajd

In Relation with PaperQ Your part of the joint installation with Markéta Othová turns to the technique of photograms. How did you arrive at it in your work?

A V The medium of photography has changed incredibly since the 1990s when I started to study at FAMU, and it keeps changing. And with it, the perception of reality in general is shifting because we see the world through images much more. After fifteen years of mainly conceptual work, I suddenly felt the need to shut myself in a darkroom. Dealing with material brings a completely different way of thinking and working. I feel that digitisation has distanced it a little from the artist. Going back to my roots thus made sense to me. Especially because we return to them with the knowledge of everything that has grown out of them over time.

Q Do you see this return as a general tendency in photography today?

A V It’s certainly not an isolated path. There’s a whole current called New Materiality which turns to the very basis of photography. It is through New Materiality that the material speaks to us again. Ancient techniques such as cyanotype, albumen print, the salt process or calotype are coming back. However, it is not a conservative return to traditions, we are still going backwards while going forwards at the same time, the medium does not have a fixed identity. The discourse of analogue versus digital is hardly even relevant anymore. It’s more about the fact that form can actually be the content of the work. I think this is also shown in the exhibition at the House of Photography.

Q What does it imply for you personally?

A V It’s a halt in the development of photography. For a moment, in this moment. A kind of inventory of the medium which an institution like the GHMP should do. But it doesn’t give answers, because there are no answers. Nowhere is it given what a photo should look like. It’s a multiplicity of ways of working, of materials, installations… Personally, I’m always most interested in the whole process that preceded the work, what ideas were invested in its creation. It is from the process that one learns, even if the final work may not be easy to read.

Q How do you think about your works? Do you know in advance exactly what they will look like, or is there room for improvisation in the last stage?

A V When you’ve been working in a medium for over twenty years, you think about it in quite a bit of detail. All of my works are preceded by sketches which I then put on paper in the darkroom. Every single picture is full of decisions, it’s totally complex. But at the same time, reading it is completely subjective, it can mean something completely different to me than it does to you. Still, I want us to understand each other on some meta-level, so that my interest reaches you as the recipient, so that you can think not through the situation depicted but through my thinking that is contained in it. What’s interesting about a photograph is that even if it’s abstract, you still approach it as a photograph that inevitably emphasizes something; we always perceive its content as real, which you can’t say about an abstract painting, for example.

Q In the House of Photography, your work meets Markéta Othová’s drawings. What did your creative dialogue look like?

A V I was attracted at the first stage precisely by that joint thinking, by that process. I knew Markéta’s other works. I like the fact that she combines graphic, careful work with photography in which she has her clearly defined visuality, her individual way of thinking which is not influenced by any transient fashion waves. When we met, different ideas started to emerge. In some of the things I was working on, we found out that they already worked the way they were, that Markéta’s input wouldn’t add anything to them. Then I showed her some more sketches and she was surprised to see that she had actually made exactly the same drawings. Suddenly, we hit a point of contact to take for a basis. Then the meeting with Vojta Märc was equally important. One Sunday, we met for three hours for a kind of associative talk. He provoked us with well-aimed questions, woke us up to the whole process and then wrote a text that is absolutely integral to the installation. But this particular connection of ours is unique; it wouldn’t have happened under any other circumstances. And it will probably never happen again.

Markéta Othová

Pictures from the ExhibitionQ In the exhibition at the House of Photography, your works meet those of Aleksandra Vajd. How do you perceive this connection?

M O I have liked Aleksandra’s photograms for a long time, they are beautiful, clean, precise, and effective. When we were looking for a common path, I realised that I had a series of drawings that were basically the same as some of Aleksandra’s photograms. In other circumstances I wouldn’t have pulled out these tiny drawings of a rather awkward nature, but in the studio we suddenly saw that they really helped each other. Perfectly precise photograms are distorted by fundamentally imperfect drawing. The awkwardness I felt was fundamentally mitigated by Vojtěch Märc’s text. The power of the intellect was able to elevate a traced ashtray to the heavens. Thanks to him, our work together took on a beautiful meaning. My shame turned almost into pride.

Q The drawings were made in the 1990s. What led you to them then?

M O I had no intellectual intentions. I simply took the objects that surrounded me, traced them on paper and made abstract compositions out of them. Or just put them side by side. I perceived it as a therapeutic activity rather than an artistic one. For me it was a way to slow down and calm down in breaks between taking photographs.

Q With the advent of digital photography, photographic art became even faster.

M O Maybe that’s why many people today are going back to the darkroom. I think we miss the manual work. We have a need to get away from the digital world for a while and the darkroom is a wonderful place. Coincidentally, that’s where the photos are made but maybe you could just sit there.

Q So you don’t see the technological developments in such a positive light?

M O There are undoubtedly advantages and disadvantages. When the camera can do everything, you have to correct the output that much more in advance. There are plenty of photos everywhere, and they’re all too perfect. But once you start thinking that you don’t want them to be like that, it’s also problematic because then you’re thinking too much about form. There is a great difficulty in the plethora of images around us. Plus, we can see them all right away, they are just a click away, we don’t have to wait six months in libraries for someone to return a book to see a black and white reproduction of a colour image.

Q Thinking about form is one of the main lines of the exhibition at the GHMP. So how do you find it then?

M O It’s actually too aesthetic for me. I like it when a photo is made kind of unwittingly, whether digitally or in the darkroom. Here everything is too beautiful. That’s why I’ve eventually become glad that I’m participating in the installation with my drawings. I’ve been reluctant to participate in photography exhibitions all my life. Any grouping of photographers somehow doesn’t suit me and I always prefer a solo exhibition or one with sculptors or painters. There I enjoy the fact that you can just make a comment with an image. No big project, just a little note. I don’t really like it when my work is presented as a photograph, because as a photograph I find it insufficient. It usually makes me very self-conscious. Putting it in that context automatically makes people look at the thing differently, and I don’t actually want them to look at it that way.

Q You yourself combine these two worlds, being both a photographer and a graphic artist. How much do you “switch” between these two roles in your work?

M O I can’t really separate them too much. I approach each task separately. For a while, in the late 1990s, I painted abstract shapes directly onto photos, and I also once made a book of poems and photos which is a combination I wouldn’t undertake now. And recently I’ve put up photos of books I’ve made myself. But when I’m taking photos, I don’t usually think about the fact that sometimes I make books, and when I’m working on a book, I don’t think about taking photos. Right now we’re working on a book of close-ups of the interiors of Rothmayer’s villa, which Martin Polák is photographing, and I’m drawing for him what the shots should roughly look like. Then, when no one is looking, I’ll sneakily take my own non-professional picture. So it’s all connected by myself. It’s like if you made a dress, then went to an exhibition in it, or did an interview… It’s still you.

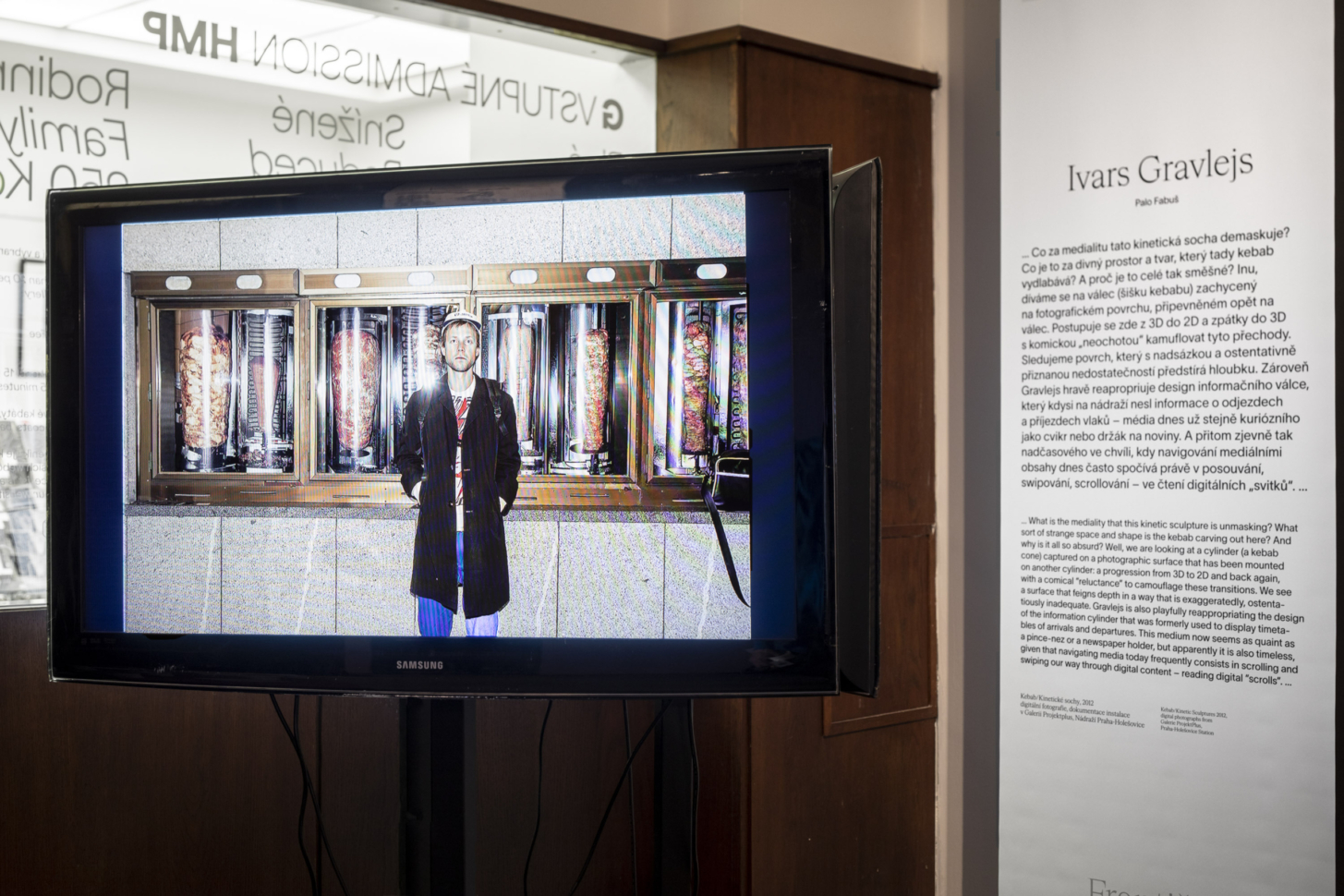

Ivars Gravlejs

Our Daily KebabAfter a period of less conspicuous activities, Ivars Gravlejs emerges with a strong contribution to the exhibition at the House of Photography. The Latvian artist, who has become as known on our scene as kebab has in Central Europe, talks about the roots of his work at the exhibition of post-media photography, which appears at the invitation of curator Palo Fabuš.

Q How did your series of kebab images end up at the Divination from a Night Sky Partially Obscured by Clouds exhibition?

I G I was surprised when curator Palo Fabuš approached me to take part in the exhibition at the House of Photography, I didn’t know he liked my work. I wanted Kebabs not to be exhibited in the same way as the first time at Nádraží Holešovice. There they had a natural place, which was the cylinders on which the train timetables were posted. The shape was parallel to that of kebab. At that time, the cylinders were no longer in use and I wanted for them to still have something to offer. Now, at the House of Photography, we have moved away from cylinders. I have long been interested in the subject of food, and the kebab – especially at the time when the pictures were taken – literally fascinated me.

Q Why? What was it about kebab that fascinated you?

I G Kebab has been something very common, everyday for some time now. At the same time, you don’t really understand it, you don’t know what’s inside. It’s the epitome of cheap fast food. It comes from a different culture: that also gives it a certain mystery, an unknowability. At the same time, it’s trash food: the fascination with trash certainly plays a role.

Q In Germany, kebab is more common and also more logical: it was domesticated there with the migration of the Turks.

I G That’s why the kebabs on display are also half German and half Czech: I photographed half of them in Berlin. I lived there for a while. I encountered the kebab theme repeatedly in various artists at the time: in the form of a giant sculpture or a rating map of Berlin kebab outlets where they were listed by their quality.

Q What do you think made them attractive to other artists?

I G Kebab is banal, ordinary: and yet it asks questions. Added to this is the visual fascination. Kebab is a subject that is quite easy to integrate into different contexts. By the way, one of my most exhibited works is the salami set. Like kebab, salami has a distinctive form and we don’t know much about its content. Food is a basic thing, its banality can be interpreted by people in the gallery differently than usual.

Q Did you speak with the kebab makers while taking the pictures?

I G Not really. It’s not that I wasn’t interested in them, but there was often a sense of stress, they suspected me of being someone like a sanitation inspector. I hoped to follow up the project with lectures and workshops, especially in Latvia, but I’ve never managed to do that. I wanted to create a performance where people-kebabs with big knives in their hands would walk through the space. We managed to make a version where children of different ages dressed up as small kebabs.

Q Do you eat kebab?

I G Not often, I maintain a different lifestyle. Perhaps when I unexpectedly need to satisfy my hunger in the city.