New Realisms in Non-space and Non-time Helena Musilová

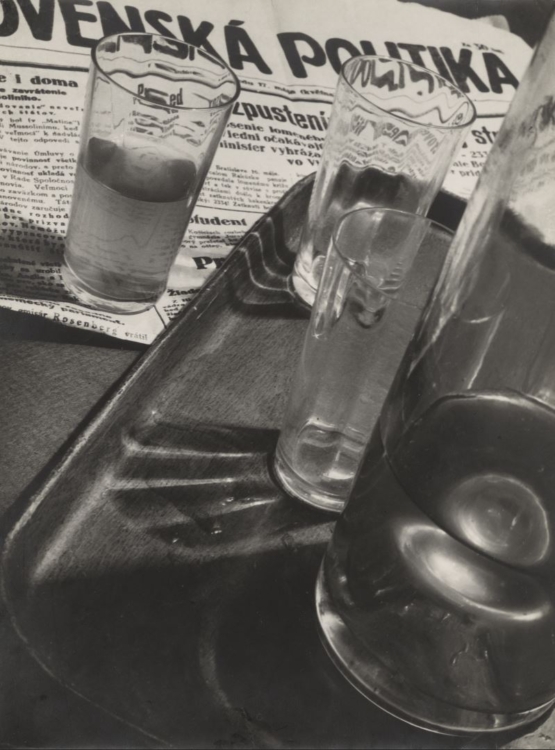

“Thus I remember how some people, otherwise quick at grasping, would not make allowance for the taking of the Paris sewerage canal, until those very same people finally arrived at understanding how expressive and almost symbolic such fragments of reality can become, where the guts of a huge city open up and the digestive juices of the metropolis are flushed out. The infernal content of a big city is thus magnified in small detail. By stopping here, the photographer has worked his magic like a magician.”

Franz Roh, Mechanismus und Ausdruck, Foto-Auge, Stuttgart 1929

Franz Roh, the German historian, art critic and photographer, summed up in a short quote the essence of modern realisms or rather New Realisms that we are trying to follow in the large-scale exhibition at the GHMP: the detail as a representation of the whole, urban life, authentic experience and the feeling that the mysterious, the miraculous exists in the seen and viewable world around us.

The idea of presenting modern realist approaches that existed in the broad period between the two world wars was conceived sometime between 2015 and 2016 but its roots are much more distant. The publication that has already come out and the exhibition which is in its final stages before being completed are the result of long-term systematic research, erudition and enormous personal commitment, especially on the part of Anna Habánová and Ivo Habán, who have devoted their professional lives to researching Czech-German culture as it was practically “taking place” in the first half of the 20th century. Both of them live and work in Liberec, which allows them, among other things, to experience and understand the reality of life outside the centre – with which (in our case, with the capital Prague, but also with Dresden, Berlin or Munich) they are in close contact while being aware of all the positive and negative aspects, which are essentially unchanged, whether concerning the present time or the period of the now idealised First Czechoslovak Republic.

This text was originally intended to be my personal commentary on the exhibition New Realisms. Modern Realist Approaches to the Czechoslovak Art Scene 1918-1945 at Prague City Gallery with some clear summary of what it is about and for whom. But it’s not that simple; the text becomes a kind of unstructured recollection of those few years with realisms. Returning to the aforementioned beginning of 2016, I am reminded of several years of extremely enriching discussions, the search for similarities and differences, the attempts to describe, understand, interconnect, rediscover authors, approaches and themes that used to play a defining role in society in their time, but which faded away in the following decade – due to changed opinions, importance, attitudes or everything else that the second half of the 20th century and its dramatic twists and turns brought. In the cultural sphere, we associate the 1920s and 1930s in particular with a link to the French art scene. However, the link to German-speaking countries was just as important, if not more so, for the real artistic activity of the time, also due to how many citizens of the then Czechoslovakia had German as their first language. The once completely natural and important “German element” and its interconnection with the “Czech one” need to be reintroduced in our history, including the history of art, which is one of the aims of this exhibition.

For Anna Habánová and Ivo Habán, the project, dedicated in its early days to the New Objectivity, and later to the more generally understood New Realisms, was and still is a logical continuation of a series of monographic or specifically-focused projects, for example, let me mention the groundbreaking Young Lions in a Cage, Art Groups of German-Speaking Artists from Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia in the Interwar Period, which, at the end of 2013, perhaps even symbolically closed the exhibition activities of the Regional Gallery in Liberec in the Liebieg Palace where the gallery had been located since its inception. Some time ago, I talked with the Habáns (as many of my colleagues call them for short) about their project of New Objectivity and, more as a provocation than with a definite goal in mind, I asked if they were also going to include photography and film, for which New Objectivity is an important chapter in their history. They hadn’t originally planned to do so, but our subsequent late-night discussion showed that a comprehensive view encompassing all the artistic media of the time could open up yet another, previously unknown or undescribed context, despite the fact that it would complicate an already difficult research process.

In the years that followed, we, that is the four principal investigators of a research project supported by the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic (Ivo Habán, Anna Habánová, Helena Musilová and Alena Pomajzlová), investigated various forms of modern realist approaches – very simplistically – on the Czechoslovak art scene and related phenomena, mainly in German, but also in Italian, Austrian or Dutch art or art in the United States, and their influence or connection with Czechoslovak art. Our aim was, as Ivo Habán summarized so succinctly at the beginning of the project: “To trace, above all, the closely related manifestations of visual art and photography, which are united by the quest for a new, penetrating and objective, i.e. factual, not simply descriptive, depiction of reality, as László Moholy-Nagy pointed out as early as 1925 in his theoretical book Malerei, Photographie, Film. One of the links between these works is also the attempt to capture the new reality of a rapidly changing modern society, traditionally associated mainly with urban and industrial environments.” The return to realistic depiction, to formal order, to themes from everyday life was also a reflection of the world’s general desire to find a firmer anchor after the years of madness of the First World War, despite the fact that the general perception of art of that period of time has been focused rather on the elitist avant-garde and the international surrealist movement.

On an ongoing basis, we have been trying to come to terms with a number of methodological difficulties. After all, they are familiar to anyone working on the history of Central or Eastern Europe: terms and dates from the “big”, Western history cannot be used mechanically; local does not automatically mean inferior or of poor quality; nor does the assumption that, within a single state or territorial unit, information was transmitted easily, even in a single language group, apply in full. For example, in the context of what was going on in the photographic scene, I had wrongly assumed that the influences of the primarily German photographic New Objectivity would be easily discernible in German amateur photography clubs in the borderlands. Added to the methodological problems is the necessity to define and constantly verify the area of our interest in geographical terms – throughout the twentieth century, the simplistic designation Czechoslovakia referred to a volatile state, that was in the process of establishing its borders only a few months after its being declared, only to emerge in a rather altered form after its restoration in 1945. This is doubly true of Slovakia as an “integral” part of Czechoslovakia. Similarly, it is almost impossible to talk about something like “Czechoslovak” art. This ambiguity, changeability and fluidity is also reflected in the title of the publication and exhibition. We tried for a long time to find a more simplistic name (which would perhaps be more visitor-friendly). Our PR department knows something about this. But eventually, we stuck to the most accurate name in terms of the content which, after all, corresponds to the nature of the works created within the framework of the New Realisms we have been investigating – the painting with cacti is called Cacti, the view of the lobby with the ticket offices The Railway Station and the sculpture of a man holding balloons is called Balloon Man. Objectivity, sobriety, and the pursuit of a concentrated message are among the common features of New Realisms in general, and we try to respect them as well.

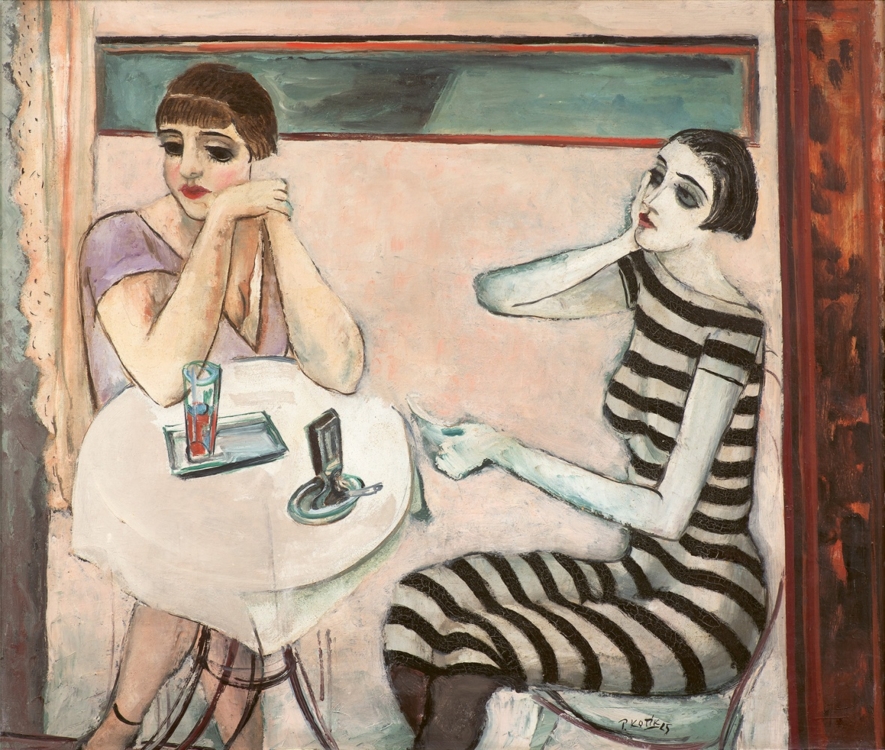

The New Realisms are not a single movement, they do not have a theoretician and a typical circle of artists who meet in a popular café, they are not accompanied by a manifesto and a radical entry onto the scene. Realism, in our case a “new” one, is understood as an approach, a certain way of depicting reality which used to appear repeatedly, or sometimes just once, to a greater or lesser extent in the work of the artists of the period under review. It was related to historical realism, to the search for “truth and beauty” of the second half of the 19th century, and it appears in a modified form in the most contemporary art, already knowing that the “realistic” image is the most perfect tool of manipulation. The New Realisms of 1918 to 1948 are connected, as Anna and Ivo Habán write in the introductory text to the exhibition: “a programmatic focus on modern life and its real problems (’as they really are’) and an attempt to capture reality in a penetrating, but not simply descriptive, manner”. Similarly, the use of the word “realism” to describe the key characteristic of a good photograph is important – it is about relating as directly as possible to the subject depicted, without the (conscious) interpretive stance of the artist.

In the course of the work on the project, more than 600 works of art and a number of photographs from all locations of the then Czechoslovakia were analysed and critically evaluated, including those that have not survived in physical form and that we know of only from period reproductions. The selection in the exhibition presents those works that do not slip into mere descriptiveness but which, on the contrary, look at the surrounding world in a new way, interpret reality and represent its essence. Art was supposed to get closer to people, but it was not supposed to pander to them. None of the artists in our milieu can be described as a “typical” representative; rather, it is their specific works that well illustrate the importance and breadth of the realistic mode of depiction on the art scene. The selection of individual works goes across traditional ethnic, group, gender and territorial divisions, with legends of Czech or Slovak modernism such as Jan Zrzavý, Josef Sudek or Mikuláš Galanda standing side by side with German-speaking artists whose work is gradually becoming more and more appreciated, such as Ilona Singer, Richard Schrötter or Paul Gebauer. Works from the field of photography and film have been combined with works from the non-commissioned arts; despite their many differences, they are united by a desire for direct, clear and non-elitist representation and a focus on people and modern life.

The structure of the exhibition corresponds to this – we pay great attention to placing New Realisms in a broader contemporary context (the timeline and map are in the entrance hall), the “circle” in the first hall represents, in two dozen works, possible realistic approaches and their position in relation to the imaginary core of the issue under investigation, which is represented by New Objectivity. Actors that follow are a world of portrait depictions of people and the individual things that surround them. The other two main halls of the Municipal Library contain depictions of the everyday world – in a “passive reality” focused on the environment, and in a “lived reality” focused on people’s lives. The cubicles present case studies, focusing on the themes of work, the reality of life outside the city or in the poorest parts of society, an interest in plants… A separate space was given to Čapek’s legendary dog, Dášeňka, which is almost a model example of New Objectivity in photography.

Realism has never disappeared from art, it has been modified in various ways – the period we are looking at ends with the end of one totalitarianism and the onset of another. Both then and now totalitarian regimes use “realistic” art as a tool to consolidate power and increase the prestige of their rulers; at the other end of the spectrum, dramatic depictions of, for example, war or terrorist attacks can provoke a radical reaction. Also with this exhibition, we want to show how differently reality around us can be viewed, shaped and depicted (not only in art) in any period of human existence.

The author is the chief curator of the GHMP.

![Richard Felgenhauer, In the Kitchen, [1930s], oil on canvas, 97×97 cm, private collection](https://www.ghmp.cz/wp-content/uploads/fly-images/29385/richard-felgenhauer-v-kuchyni-30-leta-20-stol-olej-platno-97-x-97-cm-soukroma-sbirka_1000-99999x750.jpg)