On Missing Ján Mančuška Štěpán Pech

“Becoming aware of one’s own perspective is the best way to sideline oneself,” says filmmaker Štěpán Pech of his encounter with the work of Ján Mančuška (1972-2011), about whom he made a documentary entitled Chybění (in Czech, literally: Missing) with the official English title: You Will Never See It All. The text returns to the exhibition Thinking Through Film at the Stone Bell House which featured Mančuška’s works Notion in Progress and Reflection.

I started making the film You Will Never See It All because I missed Jano. Because I wasn’t able to accept his absence.

I worked for him as an assistant. At that time, between 2009 and 2011, Jano was already working as an internationally renowned artist represented by galleries in New York and Berlin. I became part of a wide circle of collaborators that the gallerist Lizz Mulholland called “these crazy Czech fabricators”. Thanks to them, Jano was able to pour out an incredible amount of art at a speed that would have been impossible overseas. He once told me that he only had time to invent new things in his sleep. Next to his bed was an exercise book in which he jotted down ideas. His days were filled with creating art to satiate the ever-increasing demand from art fairs, galleries and collectors around the world.

The more time we spent together, the more clearly the growing shadow of his illness loomed. I remember one meeting in the studio; Jano came straight from the hospital discharged against medical advice. It was then that I understood that the idiom “as white as sheet” need not be a metaphor. I found his dedication self-destructive.

Yet the strongest emotion I have associated with him is joy. I remember him sometimes laughing so hard that he would break at the knees and fall to the ground. I was always struck by the connection between this animalistic, malicious guy and the perfect precision of thought and form in his art. He remained a contradictory mystery for me, one that I needed to deal with in more depth.

We can encounter “missing” at every turn in Jano’s work. However, as a clearly articulated theme, it appears for the first time in 2007 in the text of the same name.

“If (…) an object is absent, it refers to its unrealised presence. That is, to the fact that it should be there. In this respect, the feeling of absence is an active awareness of content through its absence.” An example for him is the place on the wall where the target once used to hang. The bullets that missed the target “circumscribe the target with a precision that is almost startling”.

It was through missing that I hoped to describe a man whose distinctive features were fullness, variety and ambiguity. But as the number of interviews I filmed about Jano grew, the more impossible it seemed to get to a clear, consistent picture. The picture kept multiplying and expanding. Individual shots and scenes became bullets aimed at the searched for object in the hope that the exact shape would one day appear.

One could say that the film about Ján is a topography of missing.

When we started working on the film, the editor, Jan Daňhel, said that the result had to be radical and egoless. That seemed to me at the time like an unsolvable puzzle. I always thought that radicality had to be based on a clear position and point of view. Reconciling the two requirements became an ever-present ambition throughout the creation process, and the key to the solution was eventually provided by Jano himself. It was necessary to listen to him.

I selected a few key works for the film. Thanks to them, situations were created in which it was possible to meet Jano at present time. “Now” might be the shortest word to describe Jano‘s work.

We rehearsed the theatre play Reverse Play again, in part with the original protagonists, and excerpts of it interweave throughout the film. Its reverse dynamics is imprinted on the structure of the entire film, which is told from the present to the moment of birth.

As Ján himself writes: “if a character (…) appears in fragments, in separate layers, (…) their identity, or even more existentially their fate, is entirely in the hands of the spectator. Because only the spectator can put it together in their mind, pressed by the feeling of the absence of a traditional hero.” The film You Will Never See It All about missing Jano, was to remain as open as Jano’s works.

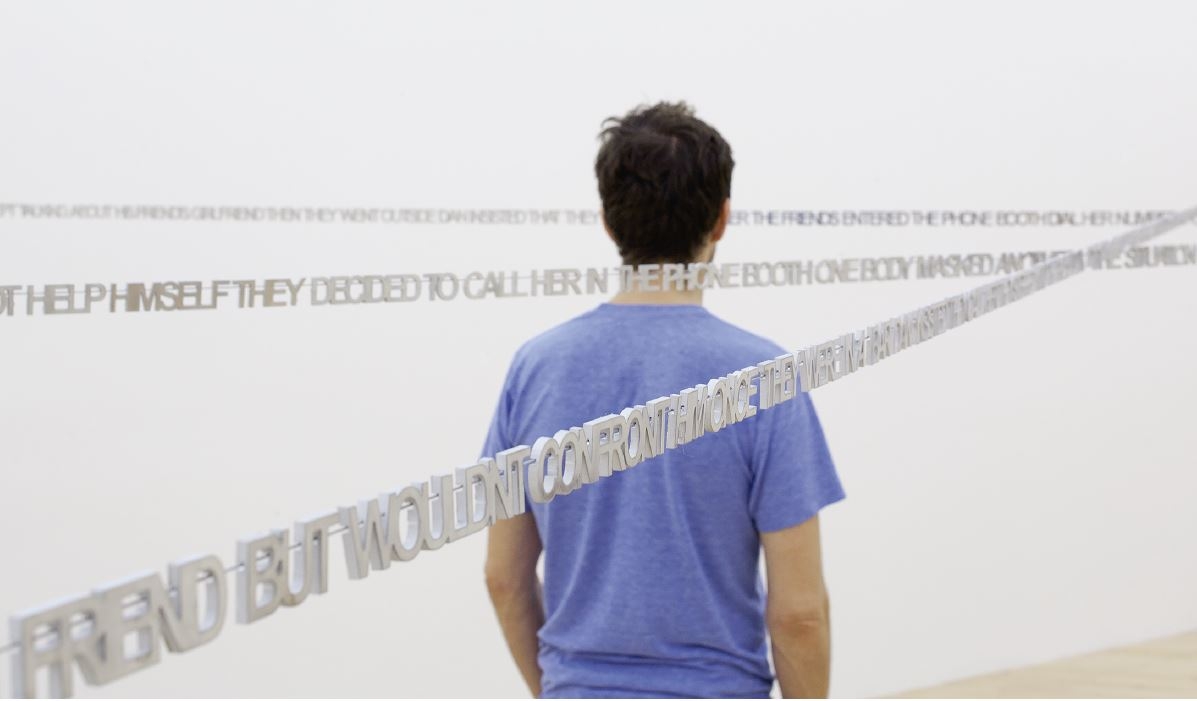

Two works by Ján Mančuška were exhibited in the exhibition Thinking Through Film: Notion in Progress (2010) and Reflection (2008). The former appears at the beginning of the film and was the first one filmed at the exhibition in Humpolec back in 2018. The latter appears towards the end, and as the film is told in reverse, it is somewhat paradoxically linked to Jano’s childhood.

If we had cut these scenes and looked only at them, one of the film’s underlying themes, that of continuity/discontinuity and transference in the father-son relationship, would have become more apparent.

When we filmed the text installation for Notion in Progress in the Osmička venue in Humpolec, our guide was Jano’s son Vojta. The moment Vojta walked through the installation, there was a flashback, a mutual mirroring of the work and a way of thinking that is genetically typical of all Mančuškas.

For viewers, Notion in Progress can be an epistemological and philosophical adventure. Only in the constellation of father and son does it also become so much more: a platform for an intimate encounter, a message, a lesson, or a contribution to understanding oneself through transgenerational transmission. An instruction on how to limit what is missing.

Reflection, the other work at the Thinking Through Film exhibition, was created for an exhibition at Ján Mančuška’s home gallery (Andrew Kreps Gallery) in New York. It is a video projection situated between two large wall systems that multiply the projected image through reflections on their shiny parts.

We see two figures having, as Jano writes in the text accompanying the work, “a dialogue that itself becomes a subject of conversation”.

Their attention is drawn to a mysterious room. Over time, we realise that it is a room full of second-hand furniture. Here again we encounter the alienation that is based on the loss of “the relationship with the beings who used to use the furniture”.

While working on the film, I began to realise why it was important that Jano as a subject was always radically absent from his works. Although his work is very often based on the most immediate, most intimate experience, it is eventually always free of purely personal connections. It opens up to the viewer’s individual experience and activity. The viewer himself thus becomes a co-creator of the meaning.

I think that this generosity of Jano’s is conditioned by his ability to retreat into the background, to allow himself to be absent. The space thus emptied can then be filled by someone else‘s experience. I see Jano’s works as an invitation to participation and creativity.

I went through many phases while working on the film. The first milestone was my ability to begin mourning. Eventually I began to realise the power of my own projection, triggered by the untimely loss of my own father. I allowed myself to step into the territory of the painful and the personal in order to search for a way to pass through this gateway to the capacity to become detached.

In the end, I came to the conclusion that only a clear awareness of one‘s own perspective is the best way to sideline oneself. And so perhaps to achieve the generality that can also be intimate.

That‘s one of the lessons I learned. That‘s how I worked my way to my own absence, thanks to Jano.