GROUP THERAPY. Collections in dialogue

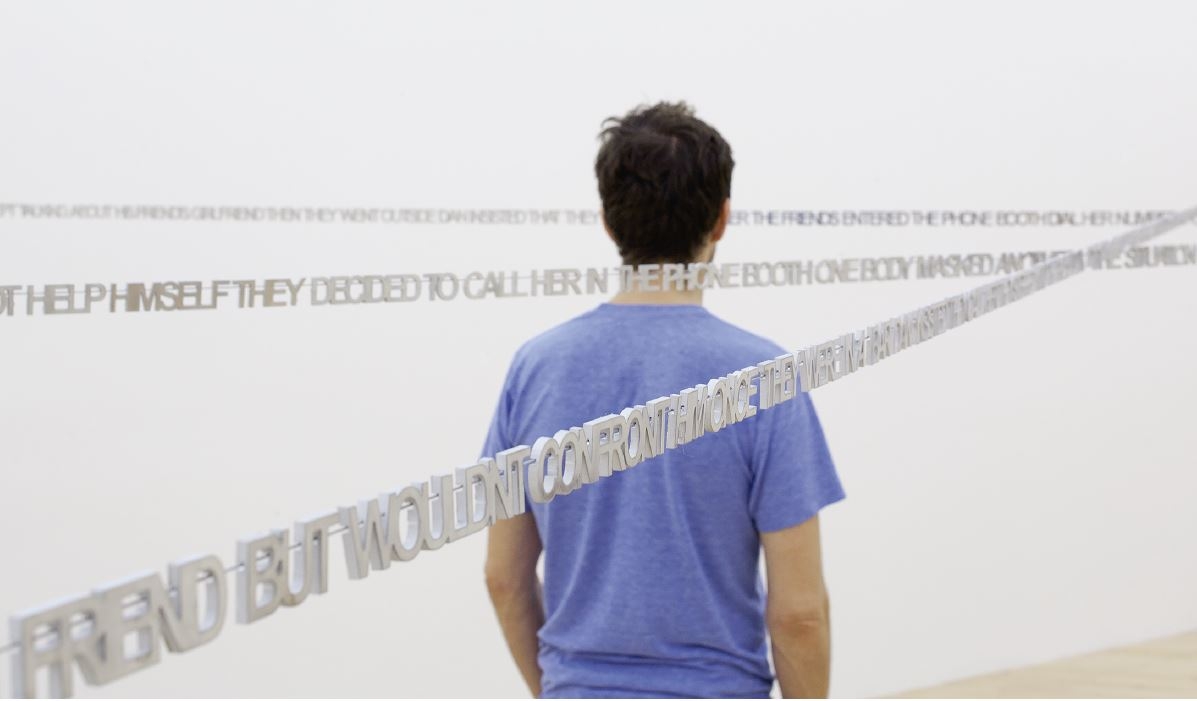

Die Ausstellung „Group Therapy“ ist als Dialog konzipiert. Sie ist eine Einladung zum Austausch von Gedanken, Meinungen, Ansichten und Empfindungen über wichtige Themen, die für die Gemeinschaft politisch und sozial von großer Relevanz sind. Dazu zählt auch die Debatte über Wertesysteme und Haltungen gegenüber einer freien, offenen und demokratischen Gesellschaft.

Die Themen haben eine direkte, existenzielle und emotionale Bedeutung für die einzelnen Individuen, die Besucher und Besucherinnen der Ausstellung, deren Alltag und Selbstverständnis davon ganz maßgeblich bestimmt wird. Die inhaltlichen Schwerpunkte haben sich aus unserem Verständnis der für die Ausstellung ausgewählten Werke ergeben. Es sind Rahmungen, erzählerische und ästhetische Felder, die alle Werke in der Ausstellung umspannen und zu denen einzelne Werke mal deutlicher und mal marginaler zugerechnet werden können.

Demokratie und gleiche Rechte für Alle spielen eine Rolle. Individuelle, persönliche Entwürfe zum Verständnis der Realität treten neben allgemeinere Konzepte, Visionen über die Wirklichkeit oder die Welterklärungen der Religionen. Der Einzelne gegenüber der Gruppe und dem Kollektiv stehen in Frage und damit auch die Grenzen, an denen Einzelne aus den Normen fallen, psychisch erkranken und mental leiden. Die Erinnerung an persönliche Erlebnisse oder an geschichtliche Ereignisse wird hervorgehoben. Die Frage, wie Erinnerungen die kulturelle und subjektive Identität bestimmen, drängt sich auf. Zukünftige Perspektiven und der Einfluss moderner Technologie auf die Gesellschaft, die Arbeitswelt und die eigene Lebenswirklichkeit stehen zur Debatte.

So bringt die titelgebende Arbeit ‚Group Therapy‘ von Eva Kot’átková, die auf der diesjährigen Biennale von Venedig den tschechischen und slowakischen Pavillon bespielt, eine imaginäre Gruppe von Menschen zusammen. Eingezwängt in ihr körperliches Korsett sitzen sie im Kreis, falten unbewusst kleine Papiere, reißen es in Stücke, spielen mit Kieselsteinen, machen sich Notizen und hören dem Therapeuten zu. In einer meditativen Übung sollen sie sich bewusst machen, dass sie Behälter sind, zerbrechlich sind, schon Risse aufweisen, sich in Einzelstücke zerbrechen lassen, um sich wieder zu sammeln und weitere Übungen auszuführen.

Während Václav Magid auf seinen Gouachen, die eine sitzende Person darstellen, existentielle Fragen formuliert – etwa, ob man privilegiert sei, wegen der Stigmata oder stigmatisiert, wegen der Privilegien – zeigt Igor Grubić wahre ‚Helden der Arbeit‘. Er portraitierte Arbeiter einer Kohlenmine, die im Jahr 2000 durch ihren Streik maßgeblich zum Sturz von Slobodan Milošević beitrugen, des letzten kommunistischen Präsidenten Serbiens, der vom Internationalen Strafgerichtshof in Den Haag wegen Verbrechen gegen die Menschlichkeit angeklagt wurde.

Die aus Sarajewo stammende Künstlerin Danica Dakić hat für ihre Videoarbeit „Isola Bella“ mit Insassen eines Heims bei Sarajewo für Waisen und geistig oder körperlich behinderten Menschen zusammengearbeitet. Entstanden sind kurze faszinierende Theaterszenen, Erzählungen aus dem Leben der zum Teil langjährigen Insassen angefüllt mit Hoffnungen, Fantasien und Zuversicht.

Von der in Tel Aviv geborenen Alma Lily Rayner, die in Prag arbeitet, wird die Fotoserie „We Walk / We Fall – An Exercise in Absence“ gezeigt. Digital manipulierte Diapositive aus den 1960er Jahren, die die Künstlerin gefunden hatte, zeigen Erste-HilfeÜbungen. Alle Gesichter sind zu einer Art Maske verformt ohne Augen, Münder, Nasen oder individuelle Gesichtszüge. Gegenseitige Hilfe wird zum Ausdruck eines sozialen Zusammenhalts. Rituale der Erstversorgung zu einem intimen, vertrauten Körperkontakt, der körperliche Begrenzungen auflöst. Diese Werkreihe wird der Serie „Negative Book“ der polnischen Künstlerin Aneta Grzeszykowska gegenübergestellt. Während eines Studienaufenthalts in Los Angeles wechselt die Künstlerin mittels schwarzer Schminke ihre Hautfarbe und verbringt so den Familienalltag. Schwarzweißaufnahmen dokumentieren sie und ihre Familie in verschiedenen Situationen. Als Negativ belichtet, wechselt ihre Hautfarbe wieder von Schwarz zu einem unwirklich kreidigen Weißton.

Albena Baeva aus Sofia in Bulgarien hat für ihre Gemälde bilderzeugende Programme eingesetzt, die mit künstlicher Intelligenz arbeiten. Sich widersprechende Suchbefehle nach Modeaufnahmen und nach Lebewesen in der Tiefsee haben hunderte von Bildern generiert, die von der Künstlerin zu klassischen Gemälden verarbeitet wurden.

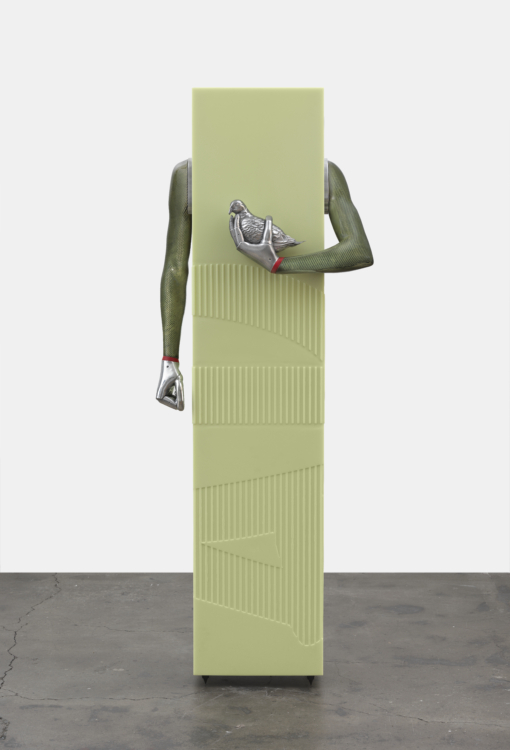

Die tschechische Künstlerin Lenka Glisníková erzeugt vergleichbare Zwitterwesen, die aus der Zweidimensionalität des fotografischen Bildes in dreidimensionale Wesen zwischen Natur und Maschine transformiert worden sind. Seltsam befremdliche organische Objekte, die wie eingefrorene Lebewesen aus einer unbekannten Welt wirken. Weit in der Zukunft und in anderen Welten unterwegs ist auch der „Agro-Kosmo“ von Anna Hulačová. Die Skulptur aus Beton und Keramik, ein Astronaut, sorgt wohl schon im extraterrestrischen Raum für die landwirtschaftlichen Erzeugnisse der Zukunft.

Der Balanceakt zwischen den immer begrenzter werdenden Ressourcen unserer Erde und der Utopie auf anderen Planeten Lösungen zu finden, wird ganz praktisch im „Mars Walk“ des slowakischen Künstlers Roman Ondak dargestellt. Im roten Marsstaub auf einem Schwebebalken sind frische Fußabdrücke sichtbar.

„Group Therapy“ ist ein Dialog zwischen zwei Sammlungen, zwischen 45 Künstlern und Künstlerinnen und ganz präzise zwischen den einzelnen Kunstwerken. Ein Teil der Werke stammt aus der Art Collection Telekom, der Kunstsammlung der Deutschen Telekom, die 2010 gegründet wurde und als eine der ganz wenigen internationalen Sammlungen ihren Schwerpunkt auf zeitgenössische Kunst aus Ost- und Südosteuropa legt. Der andere Teil der Werke stammt aus der herausragenden Sammlung der Prague City Gallery und stellt zum Teil Neuankäufe von Künstlerinnen und Künstlern vor, die in Tschechien leben und arbeiten.

Neben der schon erwähnten Lenka Glisníková sind mit Klaudie Hlavatá und Jindřiška Jabůrková weitere tschechische Künstlerinnen eingeladen worden, für die Ausstellung neue Werke zu produzieren. Zu ihnen zählt auch das Kollektiv StonyTellers, das bei der Eröffnung und während der Ausstellung einige Performances durchführen wird.

Ob dieser Dialog zwischen den Werken gelingt, ob Kunst das überhaupt leisten kann, zentrale Themen der Gegenwart anzusprechen, ob Besucher und Besucherinnen, sich auf diesen Dialog einlassen, das ist die Behauptung und Hoffnung der Kuratorinnen der Ausstellung, die von den Kuratoren der Art Collection Telekom, Nathalie Hoyos und Rainald Schumacher gemeinsam mit der Direktorin der Prag City Galerie Magdalena Juříková konzipiert wird.

Artists: Vasil Artomonov and Aleksey Klyuykov, Sasha Auerbakh, Albena Baeva, Eleni Bagaki, Daniel Balabán, Levan Chelidze, Lana Čmajčanin, Danica Dakić, Anna Daučíková, Aleksandra Domanović, Petra Feriancová, Kyriaki Goni, Igor Grubić, Aneta Grzeszykowska, Nilbar Güreş, Ksenya Hnylytska, Vladímir Houdek, Anna Hulačová, Hristina Ivanoska, Sanja Iveković, Nikita Kadan, Hortensia Mi Kafchin, Alevtina Kakhidze, Šejla Kamerić, Lito Kattou, Lesia Khomenko, Zdena Kolečková, Eva Kot‘átková, Marie Kratochvílová, Andreja Kulunčić, Nino Kvrisvishvili, KW (Igor Korpaczewski), Little Warsaw, Václav Magid, Radenko Milak, Brilant Milazimi, Ciprian Mureşan, Roman Ondak, Dan Perjovschi, Alma Lily Rayner, Slavs and Tatars, Mark Ther, Martina Vacheva.

Invited artists: Lenka Glisníková, Klaudie Hlavatá, Jindřiška Jabůrková, StonyTellers

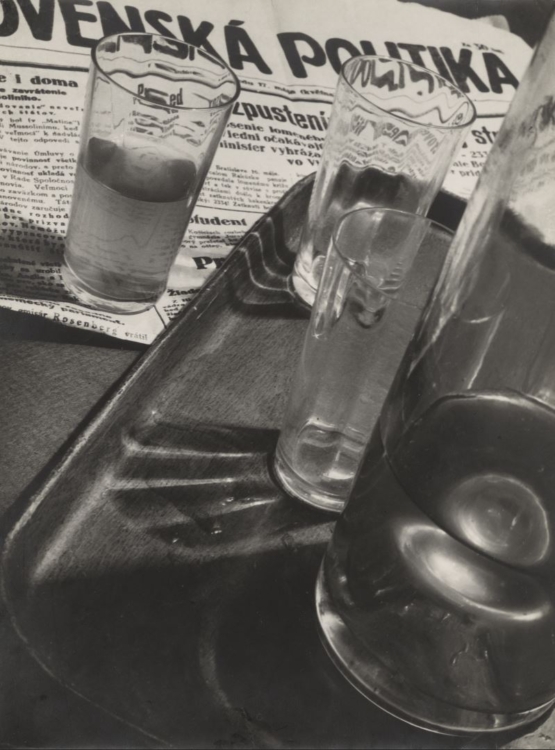

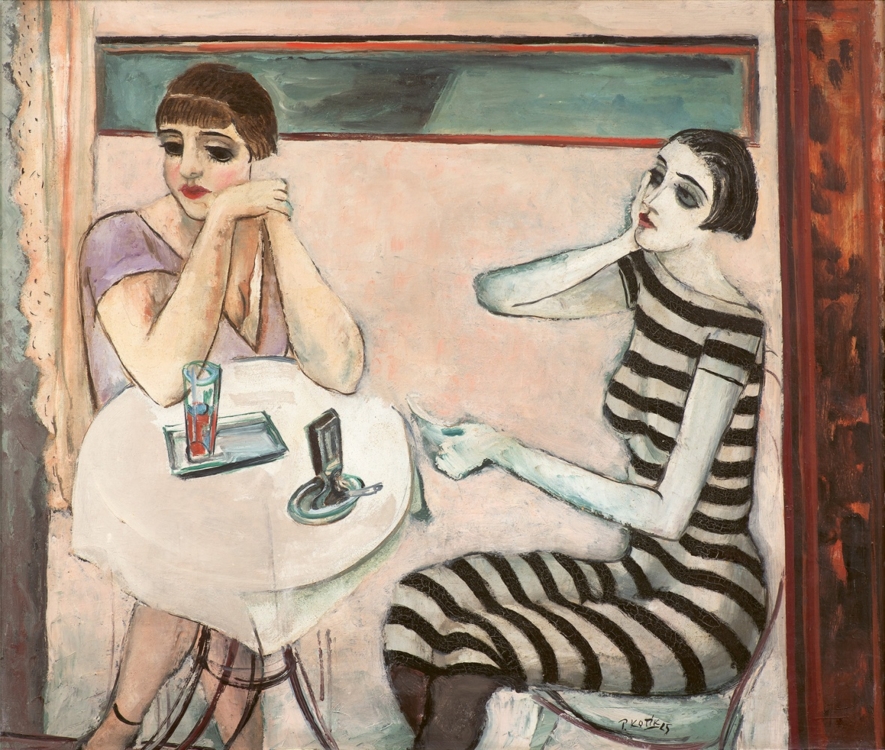

![Richard Felgenhauer, In the Kitchen, [1930s], oil on canvas, 97×97 cm, private collection](https://www.ghmp.cz/wp-content/uploads/fly-images/29385/richard-felgenhauer-v-kuchyni-30-leta-20-stol-olej-platno-97-x-97-cm-soukroma-sbirka_1000-99999x750.jpg)