The Encounter with an Image Is Incalculable

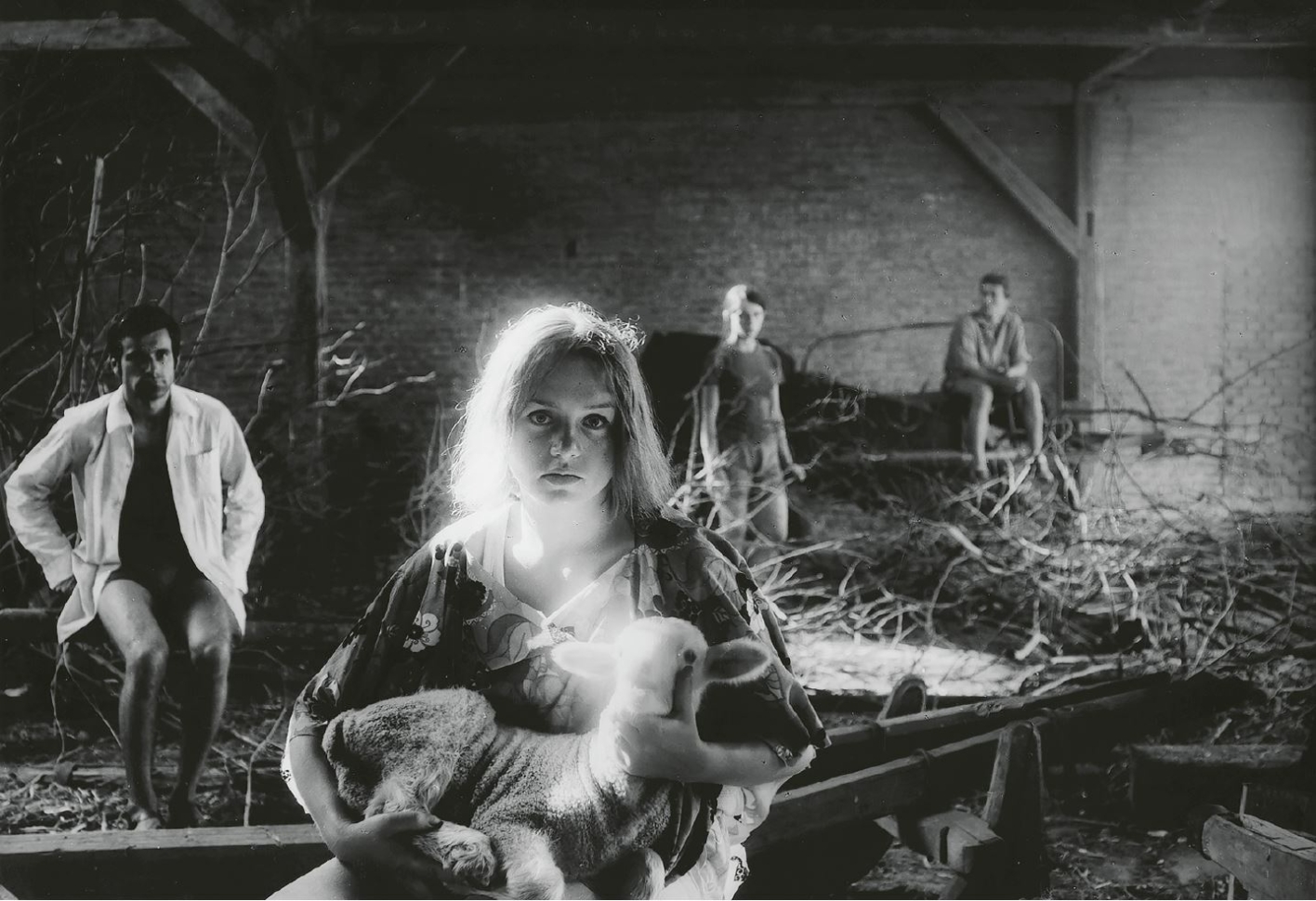

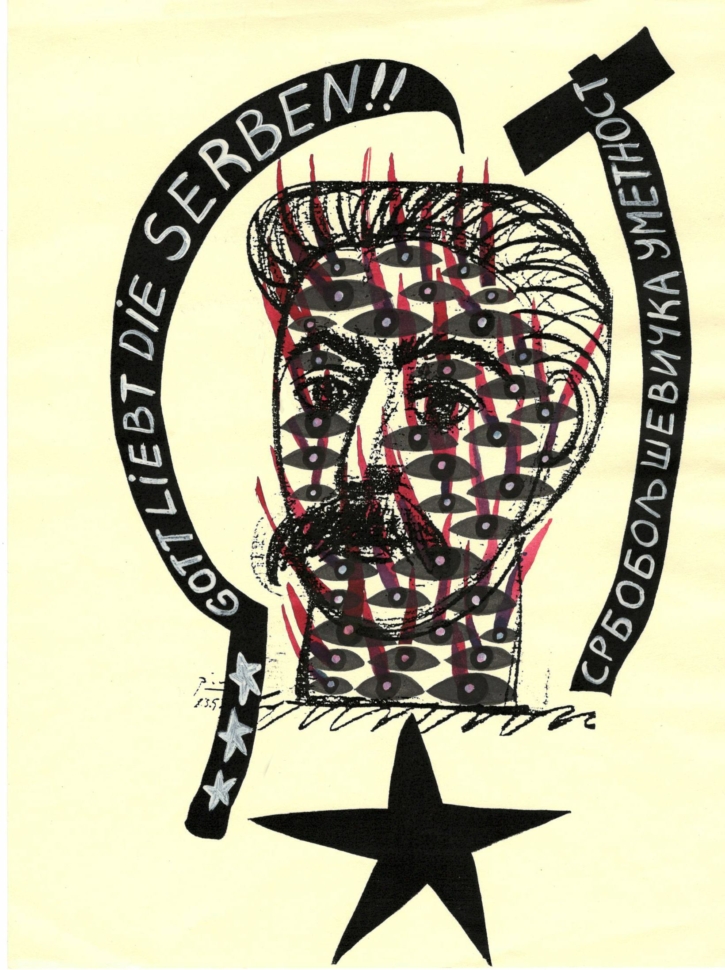

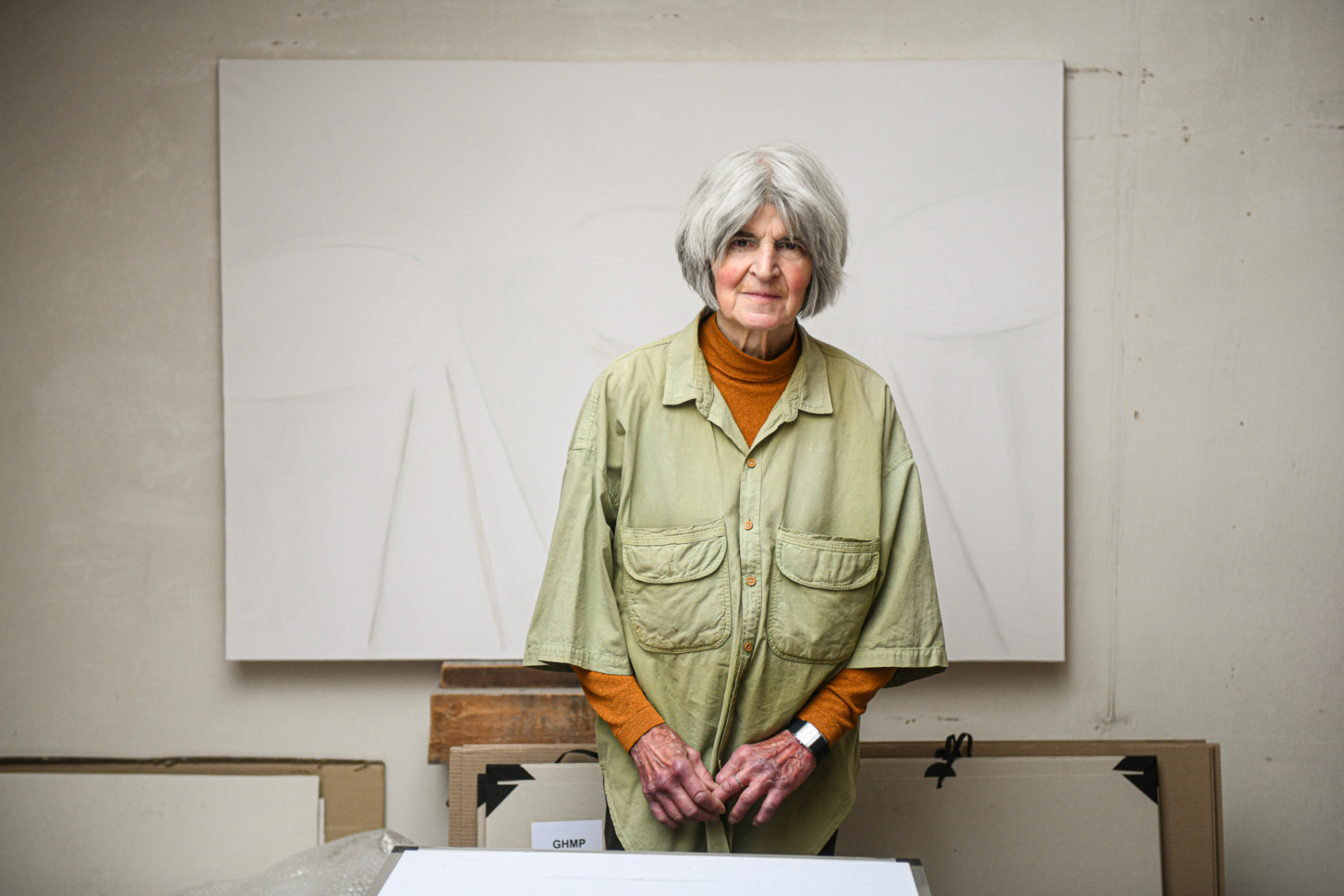

“What we need is not the hermeneutics of art, but the eroticism of art,” proclaims the text accompanying the GHMP exhibition entitled Thinking with Images based on the book of the same name by Miroslav Petříček (MP). The exhibition was prepared by curator Jitka Hlaváčková (JH) along with the philosopher Petříček, who maintains in his book that images, in effect, think instead of us and yet for us. What does it mean to encounter art erotically?

Q How do you want to exhibit thinking?

M P It’s not about exhibiting thinking. It’s about making the person who comes to the exhibition think. It’s a matter of strategy, of how to organise the exhibition so that it doesn’t just serve the purpose of people coming in, viewing it and leaving, but perhaps instead the purpose of people beginning to think about why some things are called pictures. Especially nowadays when the things that hang on the wall in galleries are not as numerous as those that are installed there, not to mention the different technologies.

J H Mirek (MP) came up with the motto based on the philosopher Merleau-Ponty that the encounter with art provokes a physical reaction which is the beginning of a process of thinking that depends on how much one opens oneself to the situation. Mirek once quoted the philosopher Michel Serres concerning how our basic position in the world can be defined, for example, by the prepositions in a sentence. I therefore perceive a work of art as a model of the world. It shows situations and ways of relating to the world.

M P In our Western culture, we are taught that we are asked questions and we answer them. We implicitly assume that when we go somewhere, we answer the question that the institution is asking. But it’s a tautology; every question actually assumes what the possible answers are, we know that from school or from tests. The point is to put the viewers in a situation where they realise that it’s not their answers that are stupid, but that they are asking stupid questions. “What is art?” This is pointless, we can go for answers to Wikipedia, where there is a basket full of answers, and even thoroughly elaborated. I would even see it as an achievement if the viewer was able to say “I like it” without being ashamed. Just like that, nothing more, not saying why and wherefore. As absolutely incomprehensible as Kant is, he has a wonderful definition that “art is purposive without a purpose”. Fascination with a work of art implies an absolute openness that points towards some sense, and I am very much aware that by any meaning, I move the sense away from me, but at the same time I hold on to the meaning and have to come up with more and more meanings. That’s why I like pictures. If a philosopher develops a distrust of the word philosophy, he or she begins to realise that the term has some sense after all. That the sense is in admitting that I don’t know the solution to some issues, that I can’t answer some questions but that I am able to benefit from such a situation. It is a situation in which something opens up. To some extent, art has a huge advantage in that compared to charades with terms.

Q How does that advantage translate into an exposition?

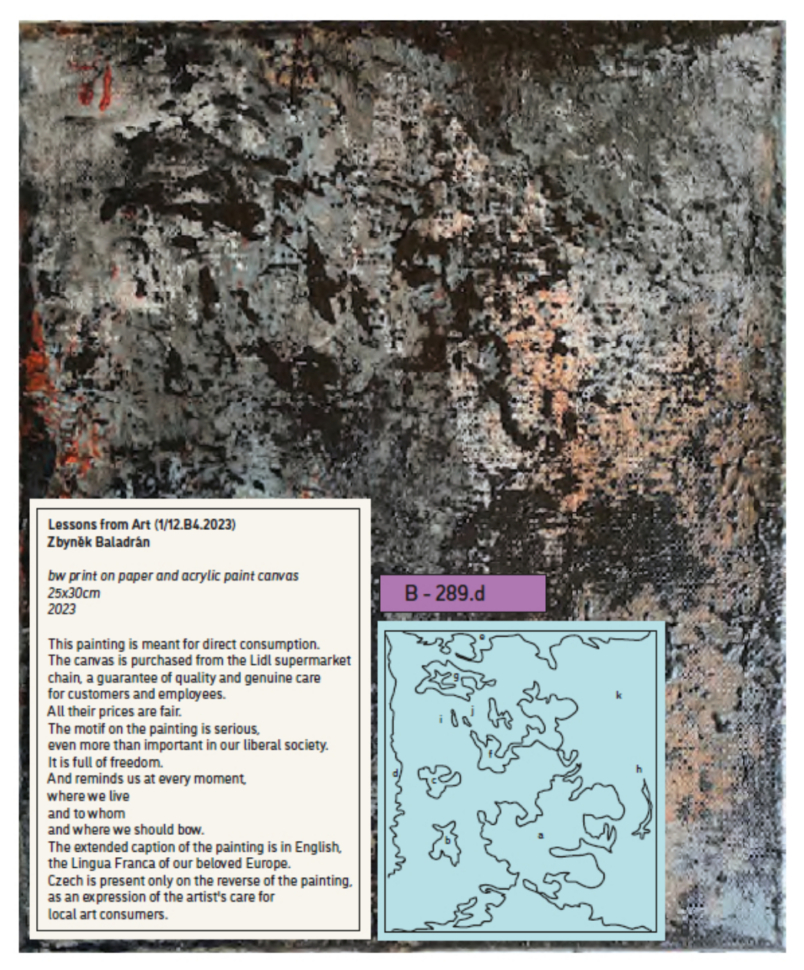

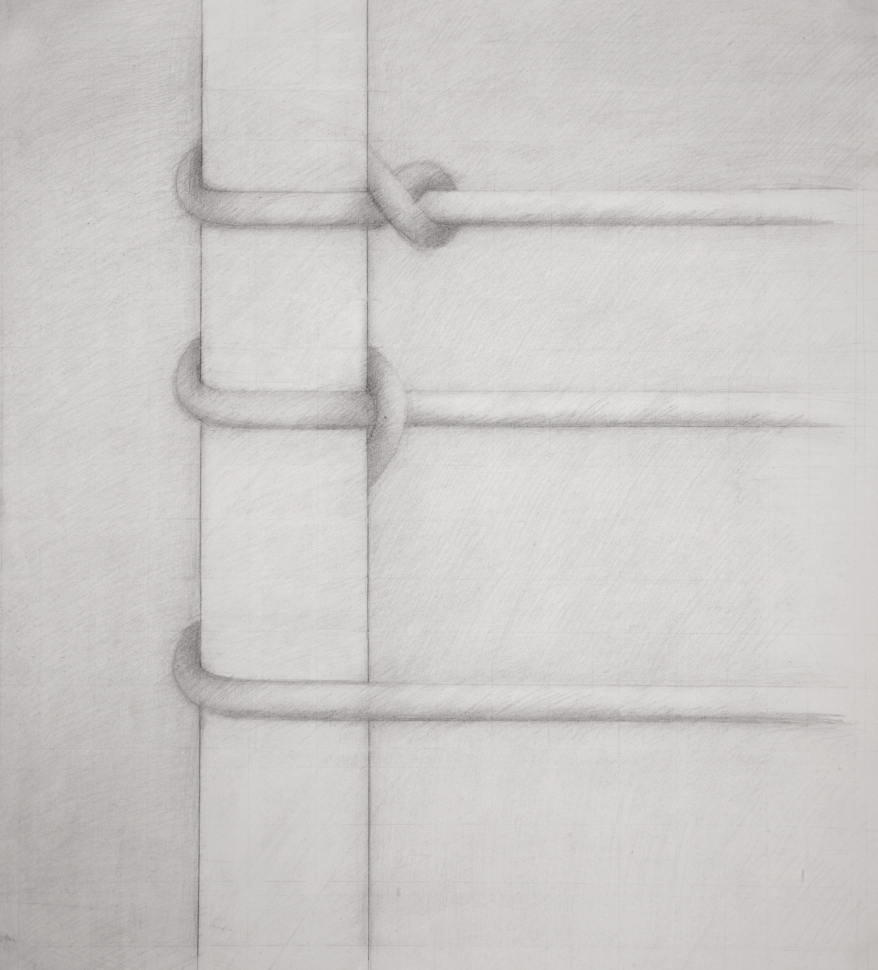

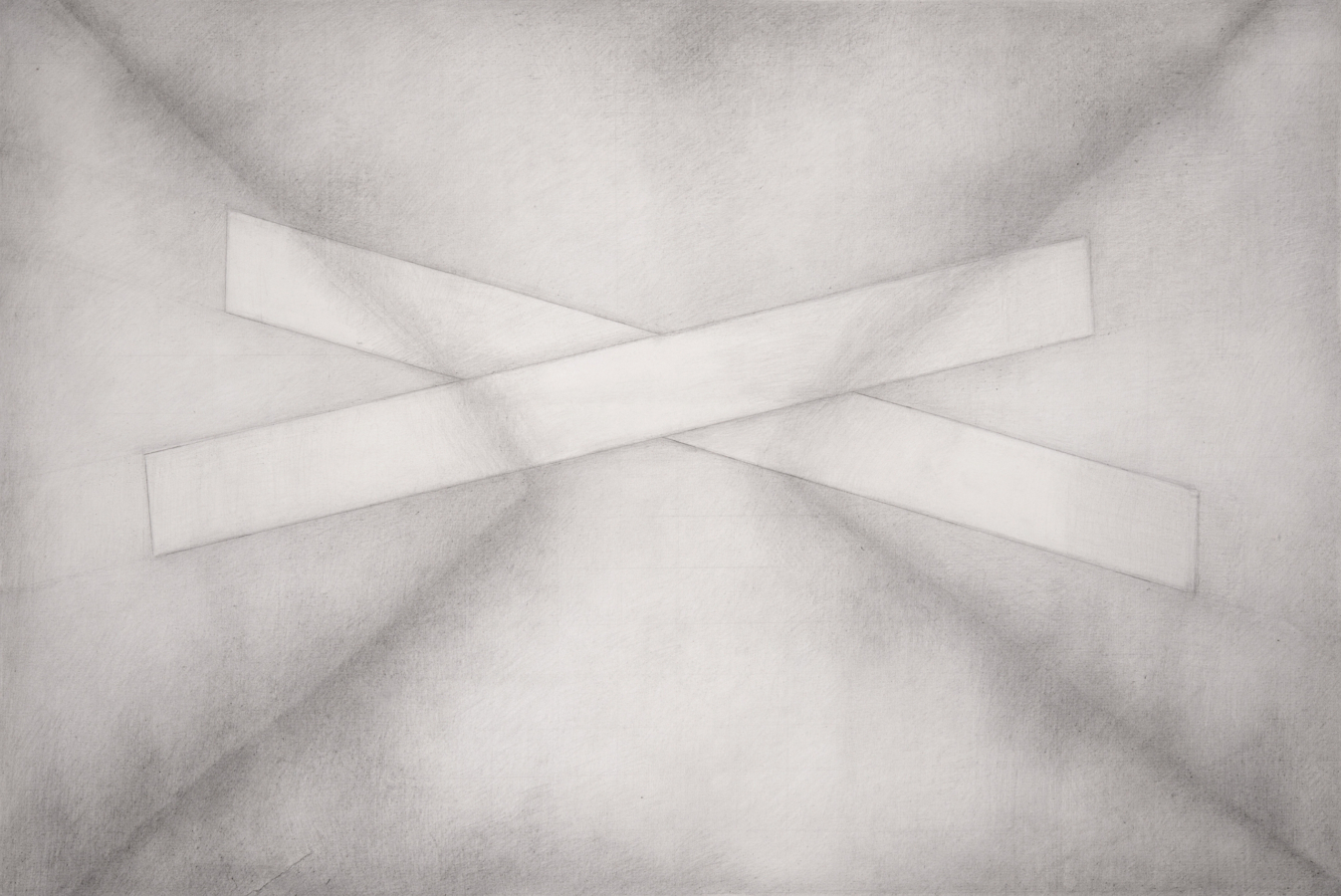

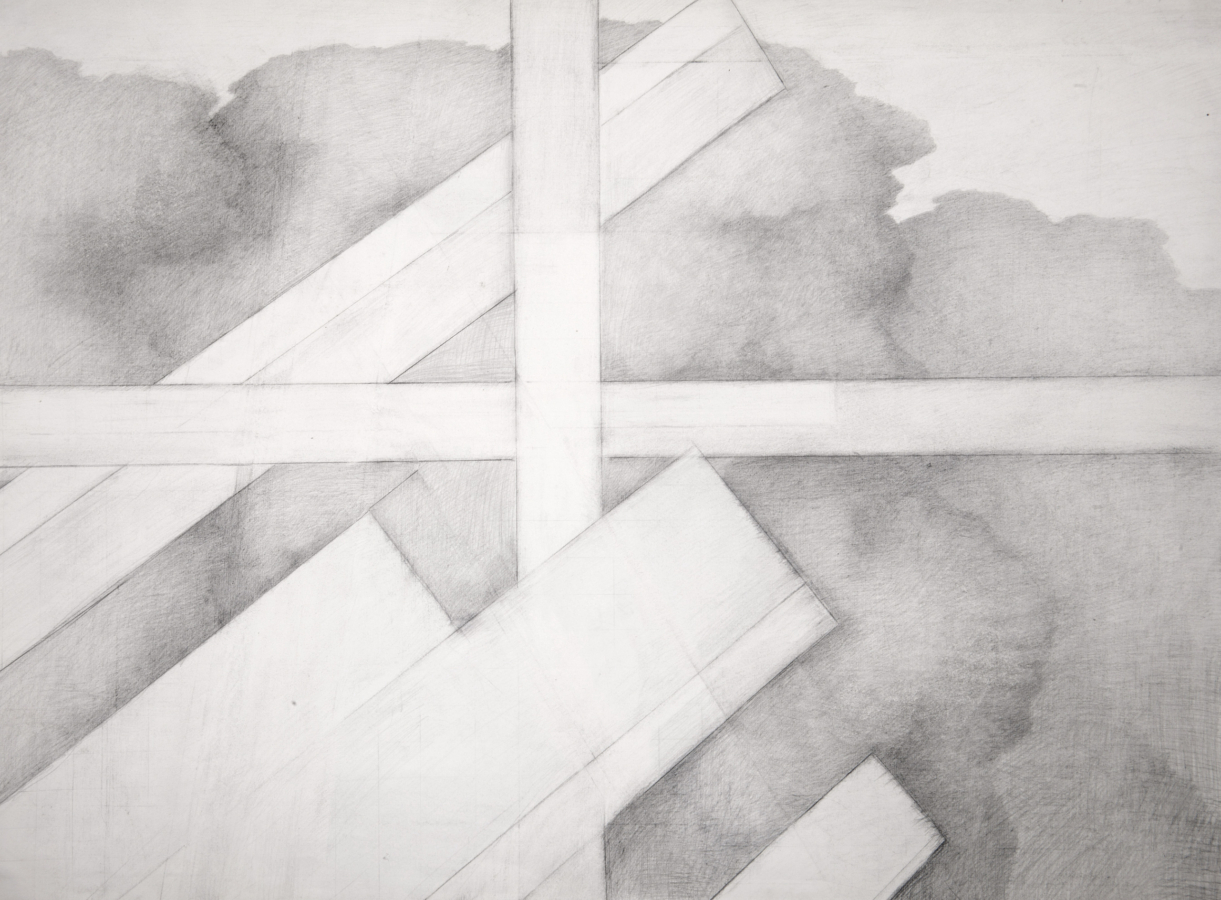

M P The viewers should, right from the very beginning, get rid of what they know. They shouldn’t walk around saying this is conceptualism and that is minimalism. They should understand, as Jitka says, that every work, or let’s say picture, is a manifestation of the artist’s point of view. And I have to adopt the artist’s point of view, to see the way they do. It means that I have to enter into a completely different relationship to the picture than just to recognise what is in it. I need to adopt the artist’s perspective. And another thing: we usually understand thinking as something that happens in texts. That’s fine, but images are a completely different medium. The moment I start reading an image and converting it into text, I lose what is inherent in images. Images provide a different way of modelling the world. That’s why it’s important to have as many possibilities as possible for what an image can be. To make things complete, an equally specific medium is the gallery itself. It too should become a picture in this sense.

J H Right at the beginning of the exhibition, still on the staircase, there should be a symbolic introduction. Along with the artist Pavel Mrkus, we are installing a kind of magical portal through which one enters the gallery while experiencing a strong visual sensation. It creates a feeling of a different space in which the usual information layers and interpretations do not work.

M P I very much appreciate what Jitka is doing as a curator because I am learning a lot from it. A long time ago, the French philosopher Jean François Lyotard organised an exhibition at the Centre Pompidou that had a crazy budget and took up an entire floor. It was called Les Immatériaux, a French neologism meaning the immaterials. It was his reaction to our time, when materiality means something else. But the interesting thing about the exhibition is that it was terribly pedagogical. The viewers were always being told what they were seeing, there was a huge flood of explanatory texts. Even though I was initially fascinated that a philosopher could do an exhibition, years later I developed a terrible distrust of it. Something so pedagogical is rarely seen. Everyone, including the architect, worked to make sure that the viewers came out of the exhibition completely educated. This is actually negative inspiration.

Q How can the lesson learned from Lyotard be formulated positively?

M P The important thing is to turn the gallery into a place where one can encounter and experience something. Not because it’s a gallery space, but because something has happened in it. The viewer should think about why pictures that are seemingly unrelated are next to each other, and look for connections. The encounter with a picture cannot be calculated. In a gallery, the viewer and the work complete each other. Why am I interested in this in fact? What is in me that I didn’t know was there and that the picture brought to my attention? For me, preparing the exhibition was a special opportunity to realise that conceptual thinking is fine, but it misses something. And that something is on the side of art. It follows that we can’t identify thinking only with concepts and texts. Problems arise – on the one hand the image, on the other the text. The exhibition should show the possibilities of how one almost flows into the other; it should show that they are not opposites. Moreover, if one looks to the books of famous philosophers that came out after World War II, most of them suddenly started talking about art. We cannot identify thought only with concepts and texts; art is not here just to be looked at and enjoyed.

Q How has the situation changed in terms of art being seen as a personal preference, an aesthetic predilection of the more educated classes or a collector’s object for the rich?

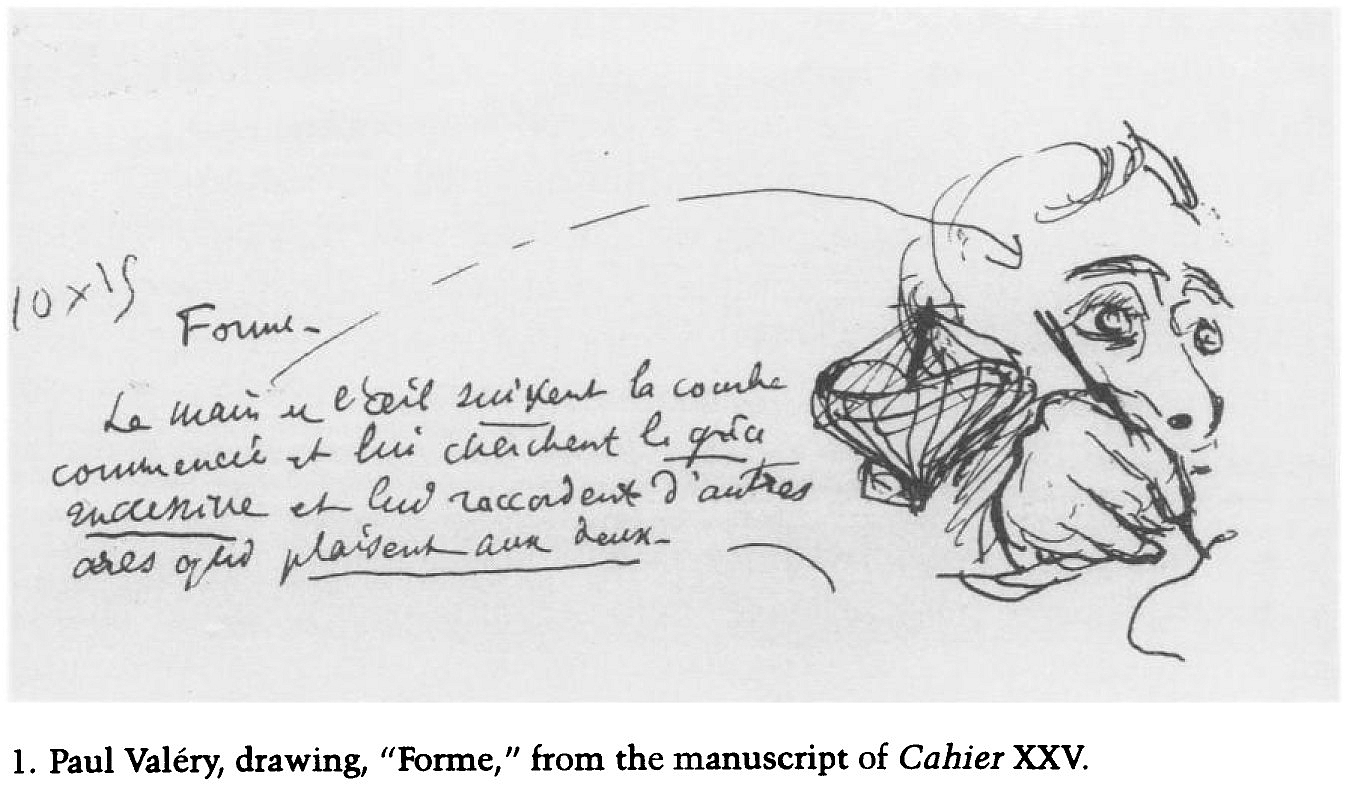

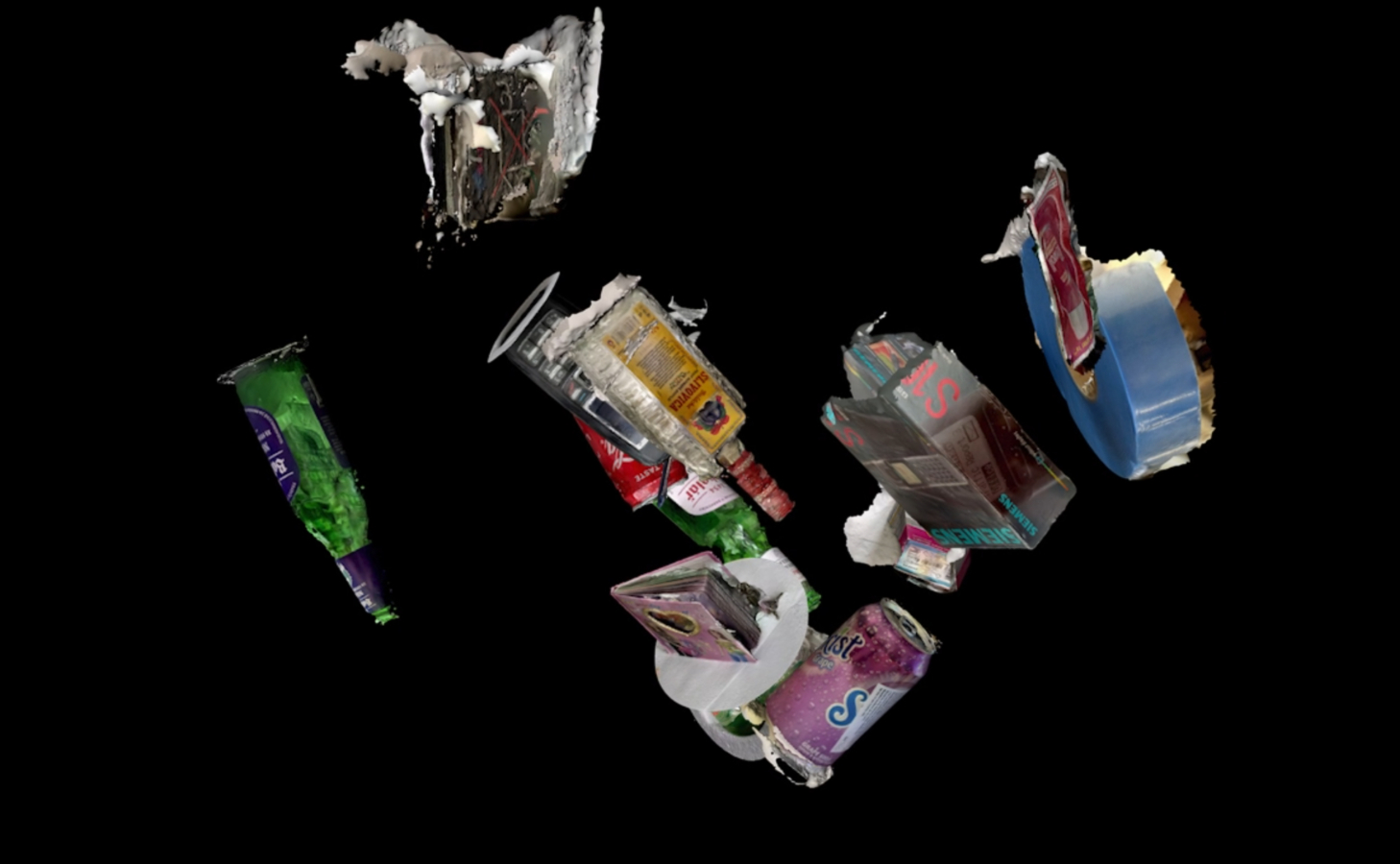

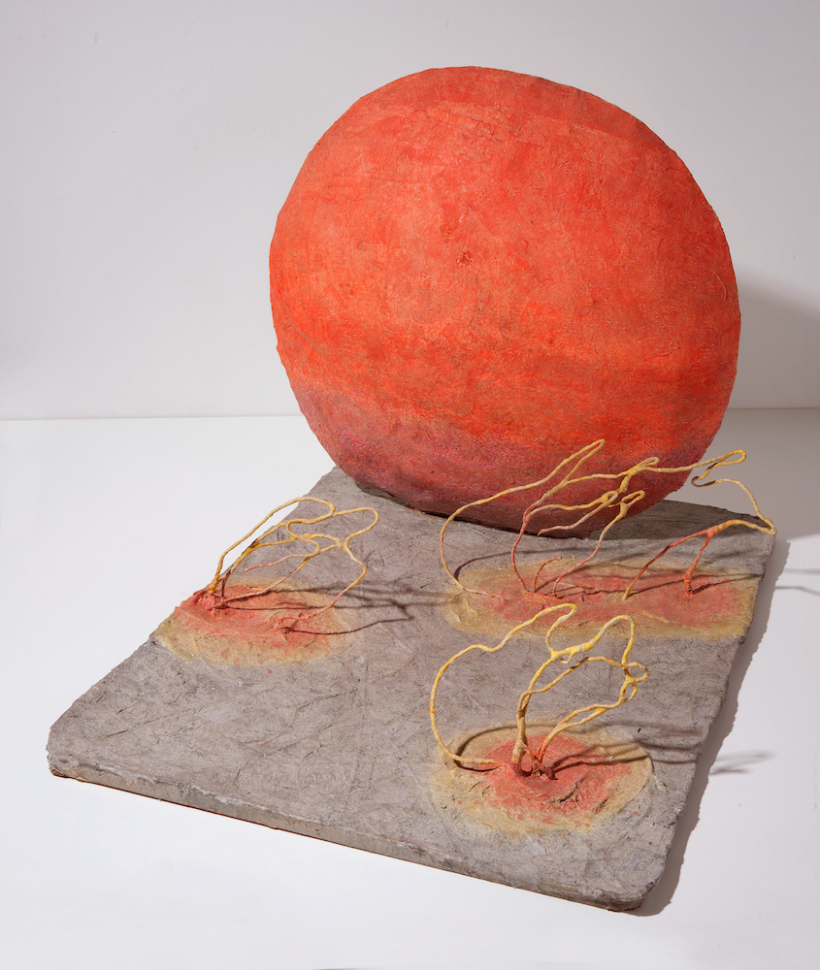

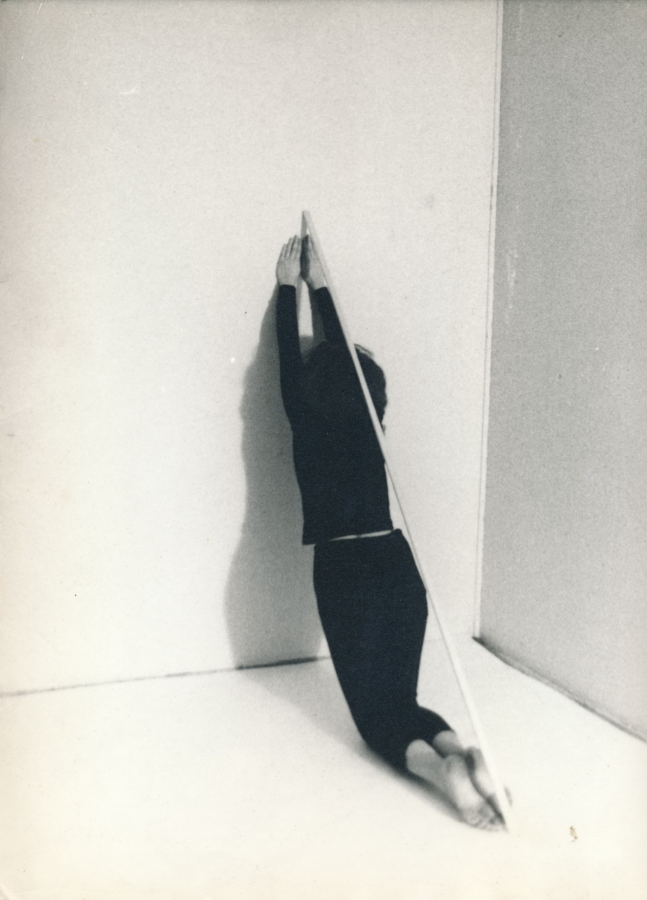

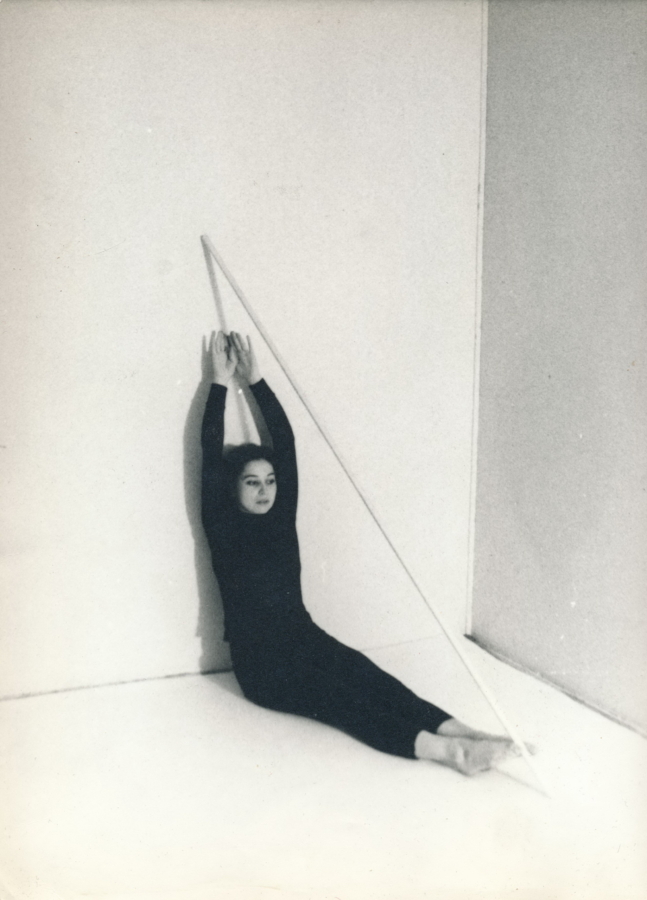

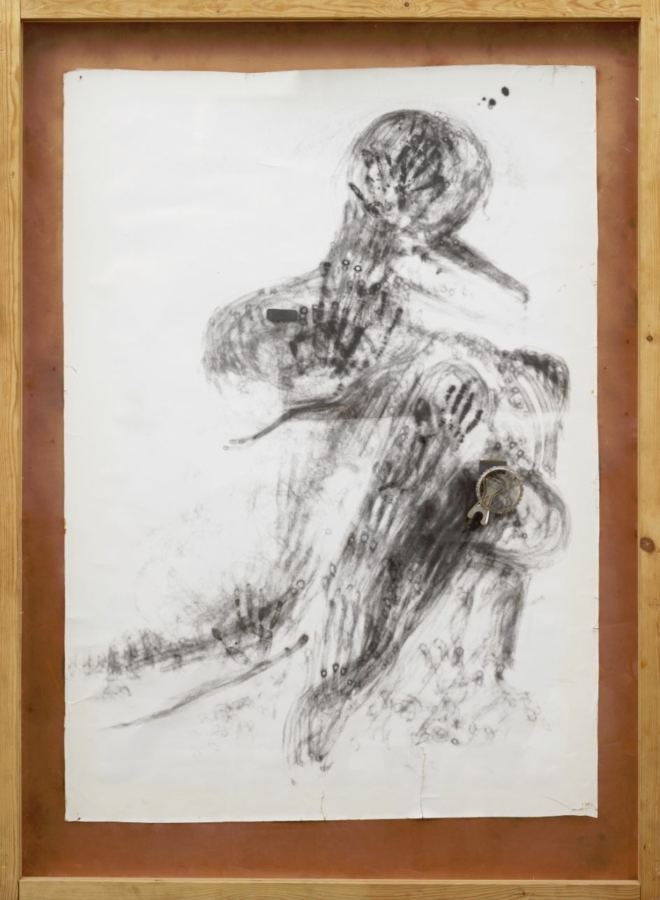

M P The situation is not so simple; there is street art, performance art and things like that. They also influence what we call painting or visual art. We would like to suggest that. A picture actually represents traces of the artist’s performance. We don’t have to talk primarily about Jackson Pollock, it’s true for Peter Paul Rubens too, for example. His hand is somehow present in the painting. And it doesn’t have to be the way Lucio Fontana does it, someone who immediately cuts the canvas. Such things are too obvious. In fact, the viewer may be struck by the fact that the painter has carelessly left a brushstroke on the painting. Why doesn’t the painter mask it? Isn’t it unattractive?! In this respect, our understanding of art must be appropriate to the 21st century. Similarly – speaking of materiality – we live in a digital world and bits are not material, yet they can become the material of artistic creation.

Q How did you select the works for the exhibition?

J H I would estimate that half of them are “Petříček’s circles”, i.e. artists with whom Mirek has worked in the past, for whom he has written texts and who may also have influenced his thinking. We are gradually adding others who somehow fit into these circles.

M P Or they crowd out mine. Which is fine.

Q What is the nature of your dialogue in the preparation of the exhibition?

M P I am fundamentally silent in this dialogue; I look and marvel. I think this is the most useful form of dialogue, one shouldn’t always be blathering and commenting on everything. When I get home, it all gets together in my head and then I edit the text, which is the source of the quote at the beginning and which should be in the exhibition catalogue.

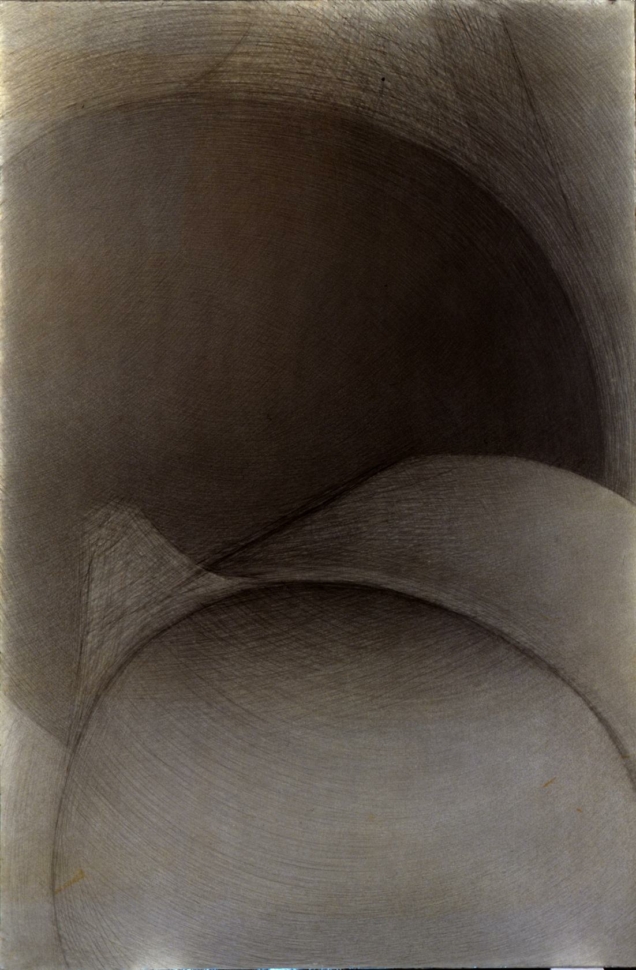

J H But that was preceded by a three- or four-year period of my listening to what you were saying and from that I made a draft structure for the concept of the exhibition, which is based on your theory that thinking proceeds from basic perception through the emergence of shapes and concepts to complex ideas. We built the exhibition concept based on that journey. Movement and walking are important aspects here.

M P So that the person who goes through it realises that even the basic, elementary perception at the beginning was nothing simple. I’m not even able to describe it most of the time. I can see a shade that appeals to me, but I don’t know what to do with it. Which is more difficult than when something comprehensible appears somewhere at the end, God forbid, like the Platonic idea of a solid or something like that. In our scheme, the visitor does not progress from simple to complex. On the contrary, complexity is presented at different levels or in different media, to the extent that we talk about perception, for example, as if we were trying to suggest that it doesn’t just mean that I see something. Without suspecting it, it’s also in play that you can touch the picture; when there’s a rhythm, it’s already somehow related to hearing. We always sort of neatly compartmentalise perception itself like that: this is visual, this is auditory, and this is tactile. Well, yeah, but when I’m in front of a really good picture, that doesn’t apply. And as far as the journey goes, each viewer finds their own way there. They see a picture which doesn’t speak to them, but another one catches their eye. The viewer finds and attempts their own journey. I think that in a gallery one doesn’t have to feel like one is going from point A to point B, that’s one of the functions of a gallery. At the same time, we try not to impose an interpretation on the works, and even less on the artists, within our own concept. We have to listen and respond; the exhibition should be our response to what they say. In a sense, the exhibition is a record of our dialogue with the artists. Arrogantly, I would say it helps both sides.