Moscow Diary? It is one of the most important articles by critic Jindřich Chalupecký. However, it does not concern Czech art and was not intended for a Czech audience. Fifty years have passed since its publication and it shows the remarkably international dimension of Chalupecký’s personality. Moscow Diary was published in the British Studio International magazine in 1973. It has the readable form of a reportage, and its readers were introduced – the vast majority for the first time – to the world of unofficial artists in the Soviet Union. Almost all of them went on in the decades that followed to become Russia’s most celebrated artists: Ilya Kabakov, Erik Bulatov, Vladimir Yankilevsky, Viktor Pivovarov, and many others. In order to remember them better, Chalupecký invented a name for them at the time, The Sretensky Boulevard School, although in reality they did not form a homogeneous group. In Chalupecký’s article, we find the first step of the successful careers of these artists: It was not political attitudes or imitation of foreign trends that started their careers, but instead Chalupecký’s fascination with the distinctive yet internationally comprehensible nature of their work. For him, their work represented a positive alternative to what was happening in art in Western Europe and the USA.

Thursday, 18 June 1972

After five years, I have returned to Moscow again. I had hesitated about making a decision for a long time; if it hadn’t been for the insistence of my Moscow friends, I would not have gone there. In the past, I had always been there as a delegate of the official Czechoslovak art organization and had been received by the sister Soviet organization with all Russian ceremony and attention. But now, I am happily a private person again and nobody can send me anywhere. Old friends wait for me at the airport and I will share their simple civic life with them for a few days. We drive across the whole of Moscow; the vast white modern districts that have sprung up in recent years and continue to grow are full of greenery and flowering trees, and I immediately feel comfortable here.

Sunday, 5 December 2021

The Jindřich Chalupecký Society sends a small delegation of Czech scholars and artists to Moscow. Their aim is to visit the surviving witnesses of Jindřich Chalupecký’s Moscow activities but also to inform the younger generation of the Moscow art community about these activities. The key figure of the expedition is Tomáš Glanc, a Russian studies scholar who has been studying Jindřich Chalupecký’s relationship with Soviet art for several decades. Over the past twenty years, he has spoken to perhaps everyone with whom Chalupecký was in contact in the former Soviet Union. Some of them attended his presentation at the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art. Glanc outlines the main areas of Chalupecký’s activities: Trips to Moscow and visits to the studios of unofficial artists during his membership in the Union of Czechoslovak Artists, as well as his later visits as a private individual. Intensive contacts through correspondence – he exchanged hundreds of letters with artists from the East – and also a bold programme of visits to Czechoslovakia by Russian artists, unsupported by any institution. A review of half a century of activities inspires the surviving witnesses to present spontaneous, not always verifiable memories. This is understandable. Chalupecký was not just one of the visitors but a real friend, a part of their lives. The afternoon meeting ends with a performance by the Stony Tellers artistic duo.

Wednesday, 24 June 1972

I first met Francesco Infante on a street in Moscow; he was almost completely unknown and utterly poor at the time – I remember him buying a bag of cheap gingerbread for lunch, munching it on the way.

Sunday, 5 December 2021

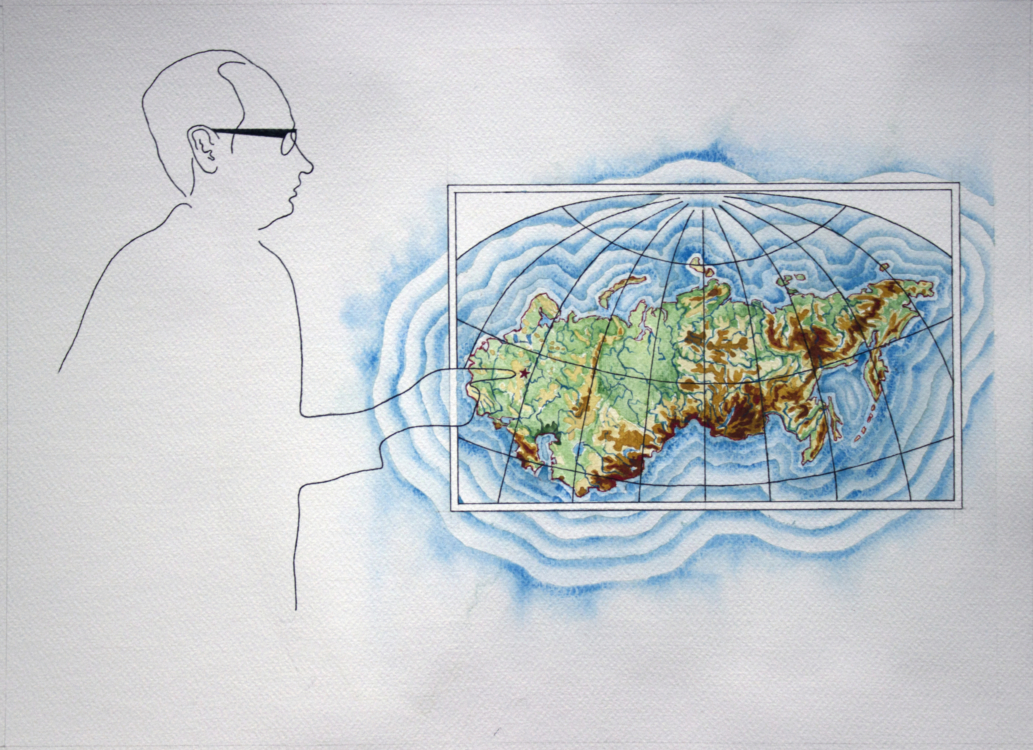

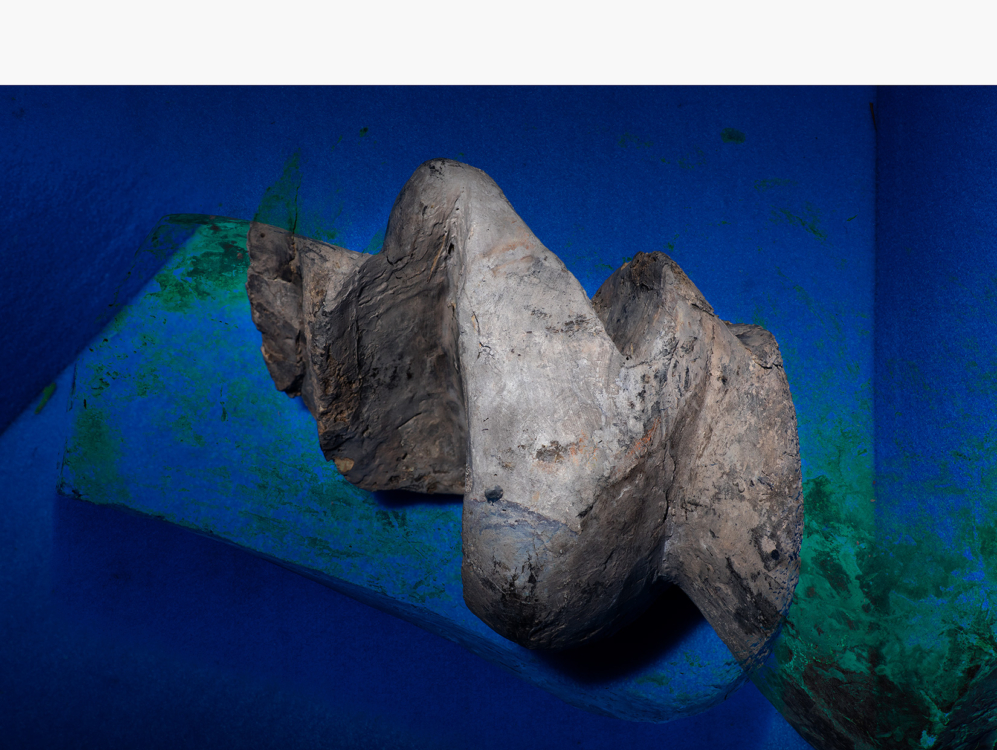

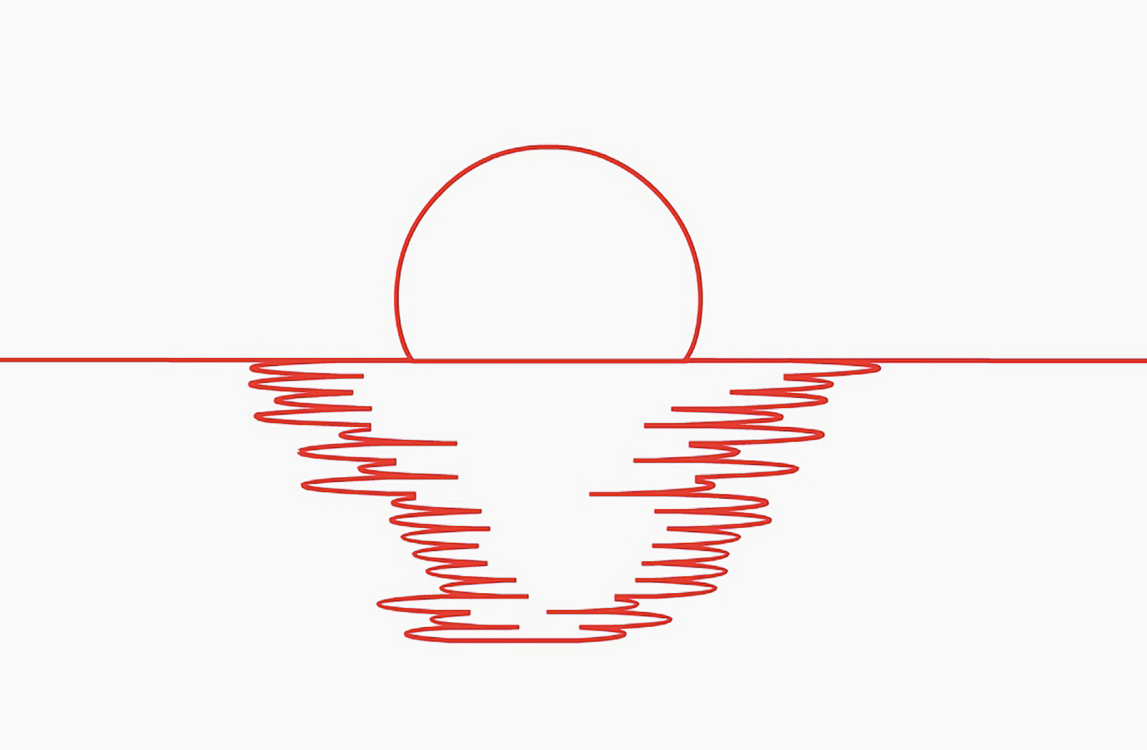

A Russian artist (with Spanish roots), Francesco Infante invites us to his home after the presentation at the Garage, a quarter of an hour’s walk through a snowy park. His apartment is both a warehouse and an exhibition of his work. We admire a spinning kinetic sculpture from the 1960s. “It’s a replica”, he says. ”The original was purchased by the Centre Pompidou in Paris”. No gingerbread is served but boiled potatoes, meat in aspic and marinated fish. Infante is an internationally renowned figure in Russian art, moving somewhere between neoconstructivism, kineticism, and land art. This is confirmed by the large number of thick catalogues of his work. ”It was difficult to learn about contemporary art in the world in the 1960s. Visits from Czechoslovakia played a key role then. Even before Chalupecký, it was Dušan Konečný.” It is clear from Infante’s account that Chalupecký was an initiatory person initiating personality for him.” He was an oddly serious geezer. He was getting on in years by then – he belonged to a completely different generation than I did – but we were interested in similar issues.” Today, we can’t even imagine how important sharing information was back then.

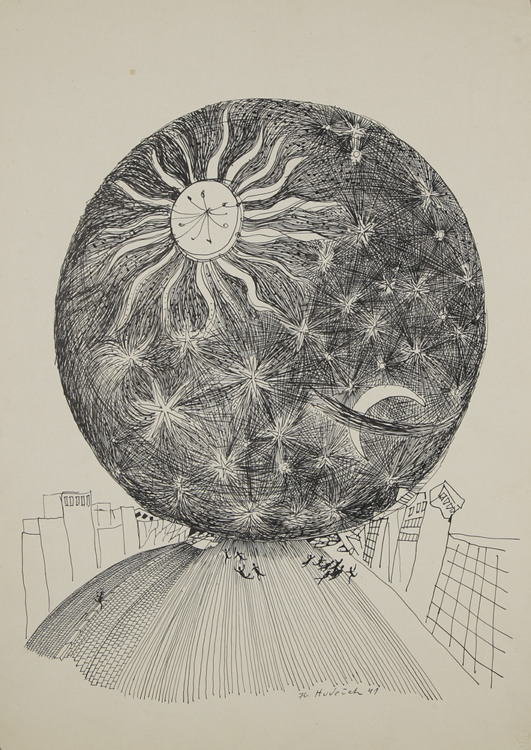

Friday, 19 June 1972

In the evening, I meet with a number of old painter friends. I know that information about contemporary art is still scarce in Moscow, so I brought my slides and tried to give an overview of what’s going on, from abstraction and pop art to photorealism and conceptual art. I also mention that art is going beyond art today, into a hard-to-define area that is close to the realm of the sacred: and at that moment everyone suddenly starts to really listen.

Monday, 6 December 2021

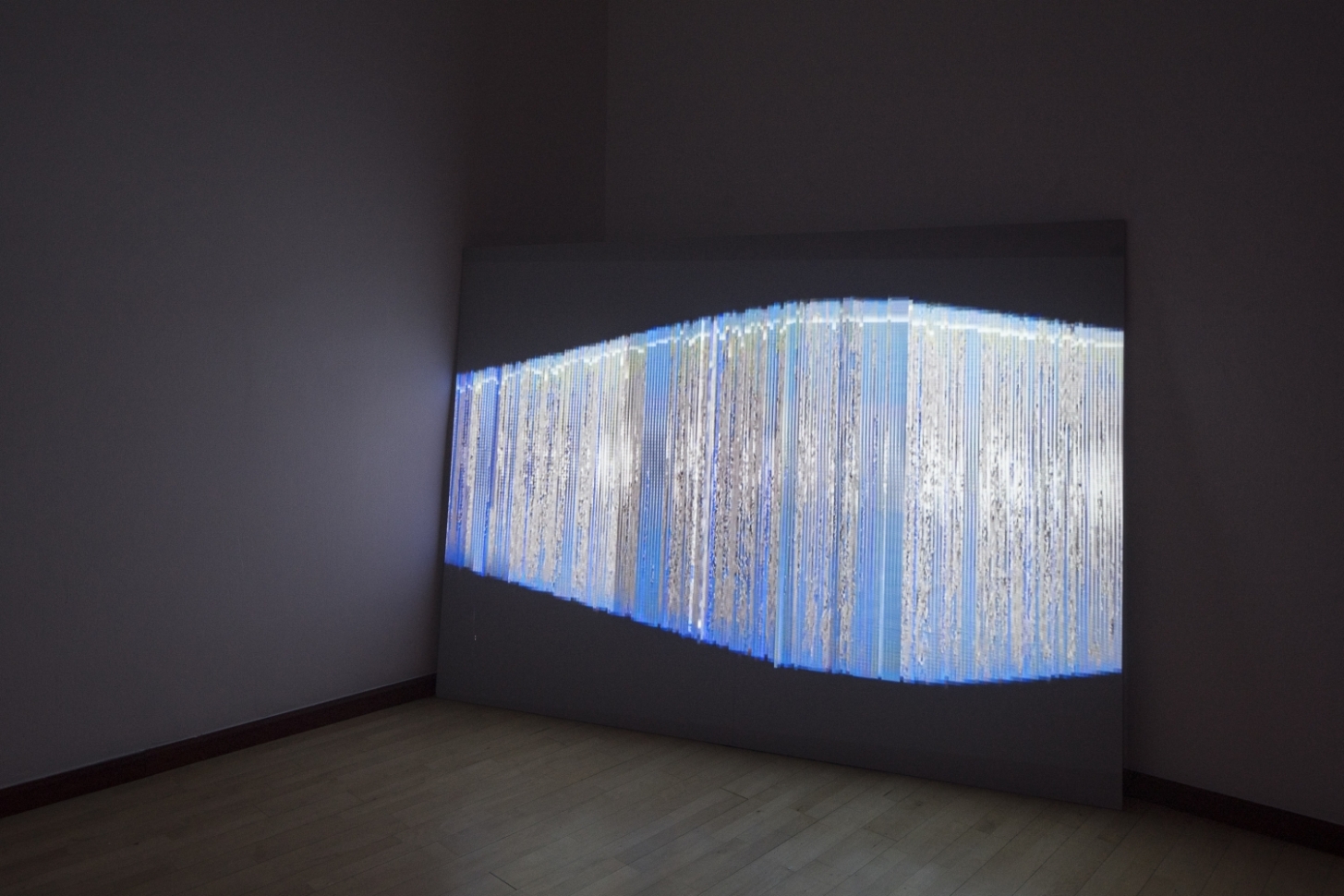

These days, Moscow is more than well-informed about contemporary art. The Garage Museum of Contemporary Art manages to combine audience-pleasing exhibitions of big names in the art world, academic research, and a popular meeting place. During the days of our visit, the GES-2 centre, a former power station near the Kremlin transformed into a similarly generous centre for contemporary art, is being opened. Here, Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson reenacts scenes from the Russian TV series Santa Barbara from the time of transformation, and he does so live, in original sets and with the original actors. The collection of post-war Russian art is housed by the already-established Moscow Museum of Modern Art (MMOMA). The exhibition on Jindřich Chalupecký at the Municipal Library will also include at least a small portion of this art. But we also visit an exhibition in a real garage, prepared by Natalya Serkova and Vitaly Bezpalov. They are better known as the Tzvetnik collective, whose carefully selected Instagram coverage of the art world is followed by 37,000 people. According to Vitaly, the path to global success was actually simple: ”Of course we don’t publish everything people send us. But we reply to everyone.”

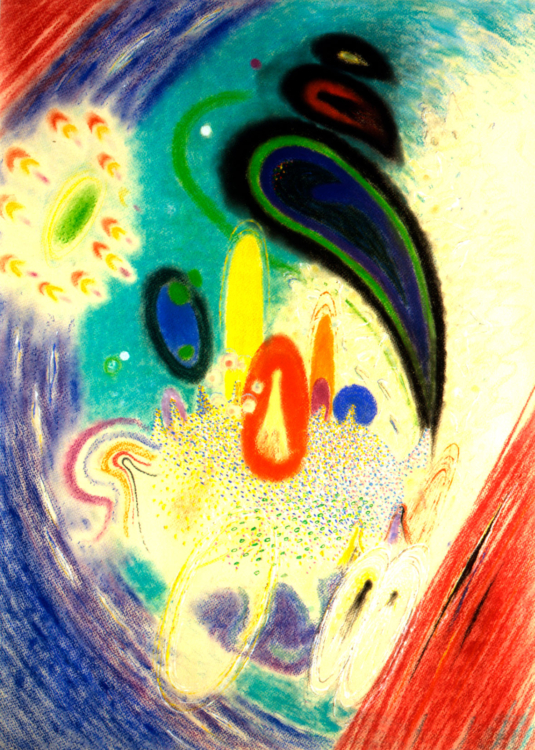

Sunday, 21 June 1972

Eduard Steinberg shows me one picture after another in the furnished room of his small apartment; but I wish I could see them hanging around in an empty space into which they could pour their white light freely – they would make the whole space abstract. It shouldn’t even be an exhibition, but probably some kind of sacred architecture. I remind Steinberg of Rothko’s ecumenical chapel, a picture of which I also showed on Friday, and Steinberg vividly agrees: it caught his eye the most, out of all the documents I showed.

Tuesday, 7 December 2021

Spirituality interested both Chalupecký and Steinberg in different ways. Chalupecký believed that in modern secular society, it was art that could replace religion. It could become a unifying element of society and allow individuals to experience transcendence, to go beyond the ordinary. Eduard Steinberg died in 2012. However, his widow Galina Manevich lives in Moscow and we visit her in her apartment, furnished in an antique manner. Everybody has to wash their hands right away, because we are about to be served refreshments. ”It’s coming up to Christmas, so forgive me if there’s no meat,” the petite woman explains why we’re having fish balls, fresh vegetables and potatoes. ”I don’t drink alone, but please have a glass of vodka with me, in memory. This one was still bought by Edik.” Jindřich Chalupecký stayed with the Steinbergs during his visit in 1974. He had indigestion problems then. He mostly recovered on the folding bed at the Steinbergs, but then had to end his trip earlier than planned.

Wednesday, 24 June 1972

Those who come to Moscow must realize that Russia is not Europe; and it is not Asia either. It is a large and complex country, a subcontinent rather than a mere state, and it must create its art out of its own great tradition and its own present reality.

Tuesday, 6 December 2021

We conduct a video interview with Anatoly Zhigalov in the snow-covered village of Pogorelovo, 500 kilometres away. The house lacks electricity; we rely on his invisible gasoline generator. Zhigalov and his partner, Natalia Abalakova, were among the Russian artists for whom Chalupecký organised a visit to Czechoslovakia. For many of them it was the first ever trip outside the Soviet Union. Immediately after their arrival, Zhigalov and Abalakova performed their tribute to Prague in the attic above the apartment of Milan Kozelka, the enfant terrible of the Czech scene at the time. Zhigalov recalls how, according to a pre-arranged plan, they visited three to four studios a day, and also went to Brno and Bratislava. Chalupecký was said to have checked whether they had really seen everything. Their guide and chauffeur was the graphic designer Jan Sekal; they are still friends to this day. He also vividly remembers a visit to, and a debate in, Václav Boštík’s studio: ”Czech artists were able to distinguish tanks from ideas. Despite the anti-Russian sentiment after 1968, I was perceived primarily as an artist. At that time, I myself rejected the socialist regime completely, I admired the West uncritically. Chalupecký tried to convince me that not everything in the West was ideal. I only approved of what he said later, when I myself emigrated to the West.” Chalupecký’s interest in Soviet art in the early 1970s, just a few years after the occupation by Warsaw Pact troops, was as incomprehensible to some of his Czech friends as his defence of the conditions under which artists worked under socialism.

Wednesday, 24 June 1972

A decade ago, a well-known critic advised sending these artists to cultivate “virgin lands” in the steppe, but today many of them have good studios and make a decent living as illustrators, graphic designers, etc., and they even no longer suffer serious difficulties due to the fact that their work is consistently published abroad. However, they do not exhibit. Thus, two arts exist side by side in the Soviet Union today, hermetically separated by the fact that one is public and the other remains private.

Wednesday, 8 December 2021

The disjunction between public and private art was, in Chalupecký’s opinion, an adequate price to pay for the fact that the artist was relieved of the pressure of the art market and the corrupting art world. Was he right? We are leaving a city full of snow and brightly lit buildings in the morning. We should come back here soon, we say to ourselves, just as Jindřich Chalupecký said in his article from 1972.

The quotations from Chalupecký’s Moscow Diary are taken from a publication called Cestou necestou by Jindřich Chalupecký, H&H publishers, Jinočany 1999.