Sugar, Body, Identity. On decolonisation with Robert Gabris and Luboš Kotlár from the i pack* collective Tereza Butková

What place does sugar have in the post-colonial world? Can we even talk about post-colonialism? And what does Central and Eastern Europe have to do with it? Robert Gabris and Luboš Kotlár from the i pack* collective, who have prepared their installation for this year’s Matter of Art biennial at Šaloun Villa, talk about the decolonisation of the contemporary world and art institutions.

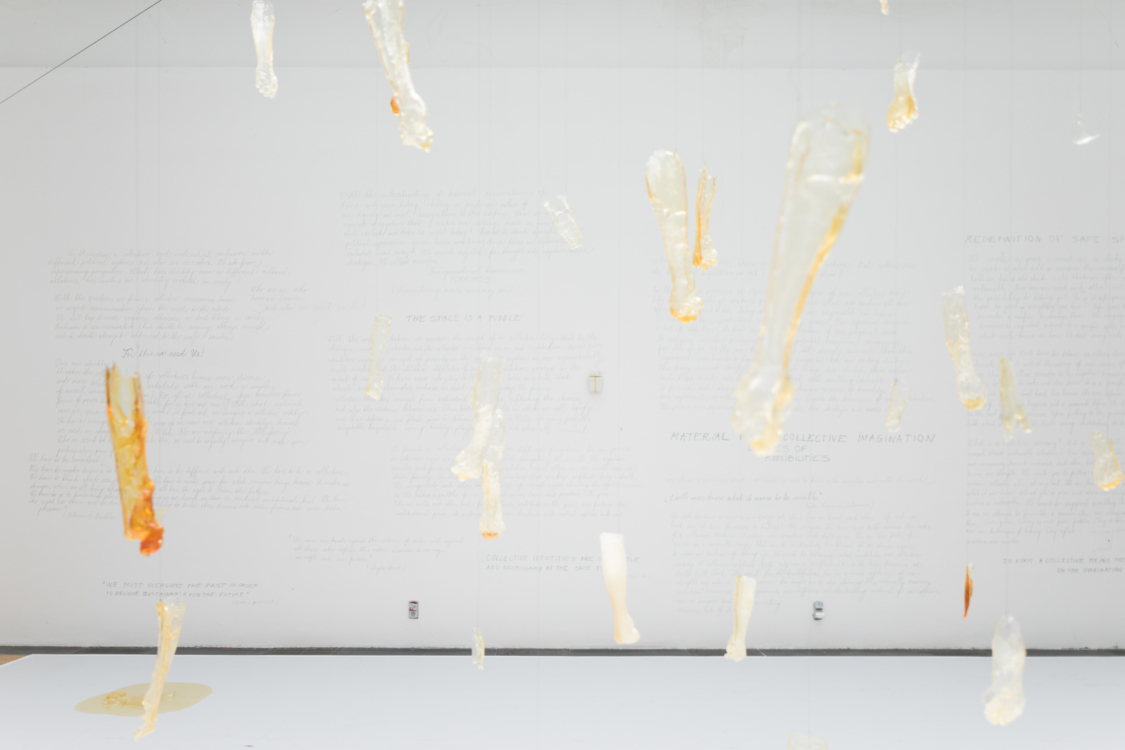

Robert Gabris originally came up with the idea of a collective work for the biennial during a meeting with Piotr Sikora, one of the main curators of the biennial. “We started talking about decolonisation discourses and I thought: How is it possible to decolonise Czech society without us, without the diverse bodies that are completely under-represented on the art scene,” says the Vienna-based Slovak artist. He then immediately teamed up with Luboš Kotlár to start preparing the installation with him. The pair had never worked together before, and each comes from a different background – while Luboš Kotlár works mainly with photography and lives in Bratislava, Robert Gabris started out with drawing and fine art. Nevertheless, they found a common way to approach their work for the biennial. “We were thinking about how we could create a collective of different disciplines and transcend our individual abilities. That’s how we arrived at the art of sculpture,” explains Robert Gabris. The resulting installation thus consists of sugar sculptures, casts of forearms with clenched fists.

T B How did the idea to create sugar sculptures come about? And how does sugar relate to decolonisation, which is the central theme of the installation?

L K We had many ideas; it was a process of experimenting with different possibilities and sugar was one of them. We knew from the beginning that we wanted to represent a body that is outside of the social norms and normalise it. Eventually, we decided to cast our own bodies in sugar and create an installation out of them. The great thing is that you can interpret sugar over and over again from new angles. It’s not just about Roma communities but about poverty in general. Everybody has access to sugar and people without resources use it all the time. Whereas it once used to be an honour to have your teeth rotten from sugar, today it’s the exact opposite. Privileged people try to avoid sugar as much as possible in order to be fit and good-looking, which brings us back to the question of the body and what society considers to be an acceptable and ideal body. The fist is a very aggressive symbol, but a sugar fist is sweet, even desirable. You don’t want to eat it because you don’t want to get fat but, at the same time, you crave it. We enjoy this ambivalence.

T B How does the reality of the post-colonial world translate into your work?

R G I’m very critical of post-colonial theories because they separate bodies from each other and try to prove why we are different from the rest of society. They divide us into minorities and majorities. The decolonisation discourse, suggesting that the process is not over yet, is much more accessible to us. In the settlement where I come from, sugar is used as legal tender and traded because people suffer from absolute poverty and hunger. So, we want to bring in this practical knowledge and show that the art world, full of academic theories, has a lot to learn from bodies that have never been invited into it. In doing so, we penetrate these institutions with our bodies and knowledge and create a new, until recently forbidden debate. Therein lies the decolonising character and explanation of our work. It is not just about artistic expression and performative media, but about having the resources and possibilities to make these facts visible. Times have changed, and new generations of Roma living in different bodies must get to work. If we don’t start doing it ourselves, no one will do it for us. Racism, exclusion, patriarchy and chauvinism have enormous power.

T B How do you feel about the openness and accessibility of contemporary art institutions? Because it might seem that art is more open to such debates than other fields.

R G That’s a lie and a cliché. We all know that institutions, not only in art, are very rigid and conservative. Art institutions are violent, they don’t allow different bodies to enter, and if they do, they often just abuse them for short-term purposes.

T B So how do you think the decolonisation process should take place within art institutions?

R G That question should be put to society, not us. The contemporary world was built by the hands of white men; we were excluded. But now we are working, we are active, and for once society needs to keep quiet, listen, and give us its resources within restitution, because our bodies are the personification of decolonisation. Let’s look at the management and structure of art institutions – the power and resources are held by a privileged few. But we need to distribute these among all of us. At the same time, it’s important to remember that we are here now, and we are putting our bodies on display by choice, even if it’s not easy. But we feel the need to speak up and contribute to building new structures. The question is whether society is ready for our entry into public space.

T B What does your decolonisation practice look like outside of the activities related to the biennial? In what ways can decolonisation be contributed to?

R G We experiment, we listen, we have many role models, we read, we talk together. We are trying to process all the anger, pain and happiness that go with it and overcome our patterns of thinking. There is no clear answer, but we are finding our own way because there are still a lot of unanswered questions.

L K We come from different backgrounds and have our own ways. I don’t have personal experience of communities, I don’t feel like a social worker, and I don’t want to pretend that I understand the problems of the people in settlements, so I support them financially.

R G Exactly. I also forward the funds of art institutions to the Roma settlement I come from. I use my privilege as a force to build a pathway to people who have no idea about art institutions. There are different ways and solutions.

T B You mentioned unanswered questions. What questions should we be asking but aren’t?

R G For me, the fundamental question is how our history can contain so many blank pages. History is reduced to knowledge that hurts. Every generation that studies history today is learning the wrong stories. It is a disgrace to society that we still do not know how many Roma people live in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, what groups exist, what happened during the Holocaust, the Second World War, and socialism. We have no statistics. Education is an absolute basic. What we have to learn at school is painful for many people because it does not allow them to discover their own history and discourages them from participating in society. To answer your question, I imagine a blank book and I wonder who should write this history? How can we be part of the reworking of our knowledge? I come from Slovakia and the society there and in the Czech Republic is apathetic. Nobody cares. Maybe we should build an institution built on caring to bring all this great knowledge into a space that we can share with others.

T B Do you see any hope for change?

R G I’m very sceptical but I find my scepticism productive. I like areas of conflict because there’s a lot of room to work in them. We are not the first or the last; generations before us have struggled and will struggle after us. For example, we can lead theatre or art classes and become role models for the next generation. We don’t have to think big to change. We can change things making small steps.