The Return of a Lost Friend Sandra Baborovská, Ondřej Vojtěchovský

In the first quarter of the 20th century, Ivan Meštrović stood alongside grand sculptors such as Auguste Rodin, Émile-Antoine Bourdelle, and Aristide Maillol. He first became known as a member of the Viennese Secession movement, but was soon able to extend his recognition further and develop his own distinctive artistic expression and stance. His contemporaries were moreover fascinated by his personal story – from an uneducated country boy shepherding sheep and goats in an inhospitable backwater in the Dalmatian hinterland, he became an exalted artist exhibiting in prominent galleries of Europe and America, thanks to his miraculous talent and to favorable circumstances. But there was yet another dimension to Meštrović’s story: in a world of “great art”, dominated by the cultural and political metropolises of the time, he represented the European periphery, where archaic feudal relations still survived at the turn of the 20th century, and where the rural population lived on the verge of starvation. To some, Meštrović was a revelation; he was proof that the underestimated Balkan Slavs were actually the bearers of a hitherto unrecognized cultural heritage that formed an integral part of European civilization.

The Czech public became familiar with Ivan Meštrović at the exhibition of the Mánes Association of Fine Artists in 1903, where he presented his works while still a student at the Vienna Academy. He established contacts and friendships with a number of Czech cultural figures and artistic colleagues, especially Bohumil Kafka. Through them, he participated in several Mánes exhibitions during the first decade of the 20th century, and he also exhibited in Prague as part of a presentation of Croatian art. His muse was the Czech Futurist painter living in Italy, Růžena Zátková, who he met during his stay in Rome. During the First World War, as a member of the exiled organization of South Slavs from the Habsburg monarchy, he worked closely with the leaders of the Czech exile, and thus became acquainted with Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk and Edvard Beneš.

Meštrović had soon become a celebrity in the broader public consciousness of Czech society; none of his fellow Czech sculptors achieved such international success. This fact, however, was no cause for envy. Meštrović the Croat and South Slav was perceived as somewhat “ours”. He proved that even an artist from a small Slavic nation could make it internationally and that the condition for his success was not to live permanently abroad but that he could work and communicate with the world from his home country. After the First World War, Meštrović settled in Zagreb, on the soil of the newly established Yugoslav state, helping to develop its national identity through artistic means, and – just as during the war – he promoted the state globally with his work. Meštrović’s 1933 exhibition in Prague was an extraordinary social and cultural event. It was visited by tens of thousands of people, and newspapers and magazines published hundreds of articles about it. However, the significance of the exhibition was more political than artistic, despite all the appreciation of the sculptor’s genius. Meštrović’s oeuvre represented the “brotherly” Yugoslavia with which Czechoslovakia was allied as part of the Little Entente. He was a friend of President Masaryk, whom he portrayed in 1923, and of the then-Yugoslav King Aleksandar I. His straddling the two countries thus epitomized this alliance, which expressed the period slogan of “loyalty for loyalty”. Czech tourist guides and Yugoslav travelogs did not fail to draw readers’ attention to the monuments by Meštrović that dominated the public spaces of Zagreb, Split, Belgrade, and other cities. In the eyes of the Czechs, his works characterized this friendly country as much as its sea, its natural beauty, and the Mediterranean or Oriental atmosphere of the local human settlements.

The affection for Meštrović as a primarily Yugoslav artist was also evident during his second solo exhibition held in both Olomouc and Prague in the autumn of 1970. During the period of incipient normalization, it was a reminder of the Prague Spring, as well as the Yugoslav support of the “revival process”, and its solidarity with Czechoslovakia after the Soviet occupation in August 1968.

Meštrović’s works are being presented collectively in Prague after 53 long years. In 2023, the 140th anniversary of the sculptor’s birth, it will also have been 120 years since Meštrović first exhibited in Prague with the Mánes Association and 90 years since his solo exhibition at the Belvedere Summer Palace in the spring of 1933.

Regretfully, we must admit that the name of Ivan Meštrović, who was one of the greatest Croatian artists, is somewhat forgotten today in the Czech Republic. However, the reason for remembering him now and drawing attention to his remarkable oeuvre is not merely out of sentiment for the First Republic. The authors of this publication and the collective exhibition at Prague City Gallery are convinced that Meštrović’s perspective and his work have retained their values and timelessness.

This is especially true of those aspects of his oeuvre that the Czech audience largely overlooked in the past century. Meštrović formed the ideology and iconography of his “national state”. But his goal far exceeded the national framework. However eagerly he advocated the artists’ need to realize and honor their roots, to him the true meaning of any artistic endeavor was to address general human issues. This humanist universalism and cosmopolitanism was also his life practice. Traces of his life, oeuvre, and artistic influences can be seen in many European and American cities where his works form part of museum collections and public spaces. Although he was a sculptor attached to his studio, his material, and his works that often were of monumental proportions, he was unusually well-traveled for his time. In his younger years, he frequently changed his place of residence. Even after the First World War, he did not withdraw from this nomadic lifestyle. After the invasion of Yugoslavia by the fascist powers, he went into exile and kept moving from one city to another, eventually emigrating to the United States after the war. For political reasons, he never returned home permanently.

In his artistic convictions and life path, Meštrović had always strived toward overcoming peripherality and provinciality. As he stated in an interview for the Czechoslovak daily newspaper Lidové noviny in 1933, “finally, an effort should be made to cultivate prolific connections between your art and our art, and also Polish art. So far, our country knows a little about your artistic production and your country about ours. Our countries are small. We could outgrow this smallness through regular contact and through becoming well-familiar with our respective cultural endeavors. You must admit how much our art would thrive if exhibitions were held more often and if artists maintained constant contact! There are local and personal groups and cliques everywhere. A South Slavic artist would be judged more objectively in Prague and your artists in our country. And the inspirational influences of one on the other would develop fruitfully.” One cannot but conclude that even after 90 years, Meštrović’s observation is still relevant.

The exhibition presents a selection of the main creative phases of Meštrović’s life covering the first half of the 20th century. These phases are expressed in the concept of the exhibition by the dominant places with which Meštrović was associated in different periods of his life: Vienna, Paris, Rome and London, where he lived during World War I, Split and Zagreb, where he stayed in the interwar period. Special space is also devoted to his successful Prague exhibition in 1933. Most of the works come from the collections of the Museums of Ivan Meštrović. However, also included are sculptures in the possession of the National Gallery Prague, including a bronze bust of Moses which was given to T. G. Masaryk by King Alexander of Yugoslavia as a gift in 1930 on the occasion of his 80th birthday. The National Museum in Belgrade also lent important works. Loans of works by Auguste Rodin from the Museé Rodin in Paris are also important.

In addition to Meštrović’s representative works, the exhibition shows period publications, catalogues, newspaper articles, correspondence and other objects, documenting the sculptor’s life and artistic career and his relationship to the Czech environment. Most of these documents are being exhibited for the very first time. Period film footage and audio recordings of dramatized letters Meštrović exchanged with his friends (Bohumil Kafka, Růžena Zátková) and his conversations with T. G. Masaryk are also presented in the exhibition.

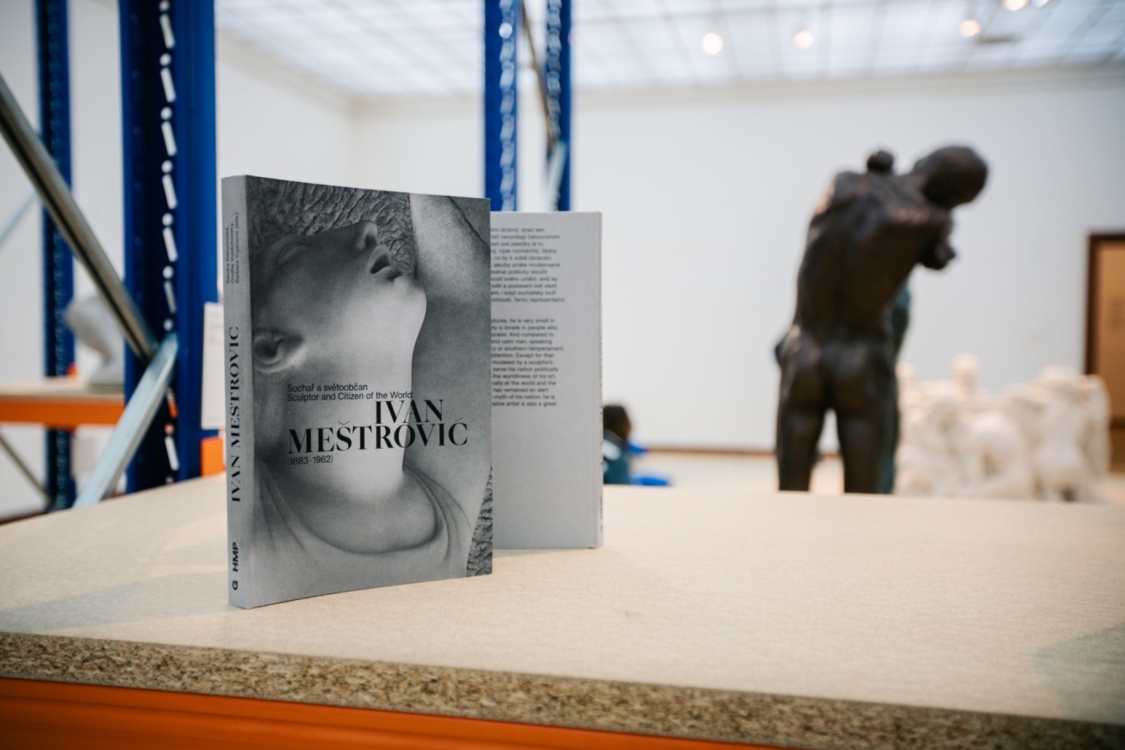

The exhibition is accompanied by a publication of the same name which is the first independent book dedicated to Meštrović in fifty-two years. It contains studies by Czech and foreign authors who have recently explored various aspects of Meštrović’s work and life, and it also brings previously unknown or unused documents, such as reprints of articles on Meštrović written by the leading Czech art critics of the interwar era. From an artistic point of view, the photographs of Meštrović’s sculptures taken by Josef Sudek during the Prague exhibition in 1933 are extraordinary.