Understandably, I espcially wanted to discover the things that they didn’t talk about at school, the poetry that, just like back home, was certainly hiding in dark, out-of-the-way alleys and abandoned, forgotten corners, the pulsating life in places where the the firm hand of state power could not reach. While on my first scholarship, my classmates and I bought ourselves Flying Pigeon bicycles and set out on our journeys of exploration. Parallels are a tricky thing. There was no Chinese equivalent to [the Czech punk band] Psí vojáci. Besides, as everyone knows, it is a big country, so try finding a needle in a haystack. Similarly, everybody knows that a foreign and anonymous observer will always see what they know, what their powers of perception are capable of identifying.

At the legendary artists’ colony of the Old Summer Palace, we found only shadows of its bygone fame. Some construction was being planned, the place attracted far too many gawkers and adventurers, and the painters had long ago moved elsewhere. On the out-of- the-way sidestreets, we passed plain-looking villagers with bags over their shoulders, who shouted at us the entire time we walked down the street: foreigner, foreigner! The guaranteed authentic Beijing opera performance at the tea house was upon first glance an overpriced tourist attraction. Every trip was an adventure, but each ended differently than we had imagined.

The world around us continued to let us know that it was high time to take off our rose-tinted glasses. You can pretend all you like, but a green light really does not mean that you can cross the street without being hit by a car, motorcycle, speeding tuk-tuk, or aggressive bicyclist. Despite all its outward otherness, however, we still stubbornly felt a strange sense of belonging to this world. Back then, “China” was definitely not an enemy in the public space. After all, Chinese students had only recently been protesting for the same ideals as us, had gone on hunger strike, had risked and sometimes lost their lives in the name of freedom. The streets were abuzz with day-to-day life, and the rest we find in books, films, music. At the time, director Zhang Yimou and others celebrated success at European festivals. Even Czech Television’s “nighttime film club” showed a series of Chinese films. Out occasional little discoveries sometimes took on unexpected form, but that just made them all the more interesting. In the end, I didn’t fulfil my dream of seeing a rock concert by Cui Jian until ten years later. By then, it was a new millennium and a new ruling class. The arena was filled to the last place. All the tickets were for seating. An impermeable line of police stood tight together between the stage and the audience, all around the bottom, in the middle, and up in the galleries. And yet, when the rocker took to the stage the arena roared and never calmed down. He played songs from his new album, but towards the end of the concert, when he hit the strings and launched into A Piece of Red Cloth, the audience jumped from their seats and absolutely everybody sang along.

In the end, I even met those underground poets. Not in the underground, but at an event with a red fabric across the entire stage, with a lot of applause. Some young guy stuck a poorly printed publication in my hand, told me there was a contact in it, and disappeared. Later, my friend and I met with three poets and read their poems from this samizdat collection. We also translated a few into Czech. One of them continues to write poetry and to encourage young people to be creative, another is still publishing poetry collection and also makes documentaries, most of them on social issues. However, due to the large competition, his documentary about rural children who have to choose between a basic education and life with their parents in the city, and about the activities who try to help these families, did not make it to the One World festival in Prague. The same thing happened with his documentary about orphans. This year, he didn’t submit any film. In the spring, he suddenly disappeared and nobody heard from him for about two months. Then he reappeared, but not his manuscripts and film material. He has to stay home for a year and is not allowed to go anywhere. But he is writing again.

The further removed we are from our nineties, the more painful it is to return. Today, it feels as if everything has been swept away by time. The observers took off their rose-tinted glasses long ago, and “China” is again being talked about as an enemy. Foreigners see supermodern buildings – the dirty, out-of-the-way alleys have been demolished or redeveloped. Red banners in the streets and slogans everywhere are ever more aggressive reminders of who is in charge. And yet the country lives. For those who want to see and hear, that earlier time still resounds in the undercurrents. Its ideals may have officially fallen with the coming of the tanks, but they did not die, at least not as long as there are people who lived these ideals and continue to pass them on.

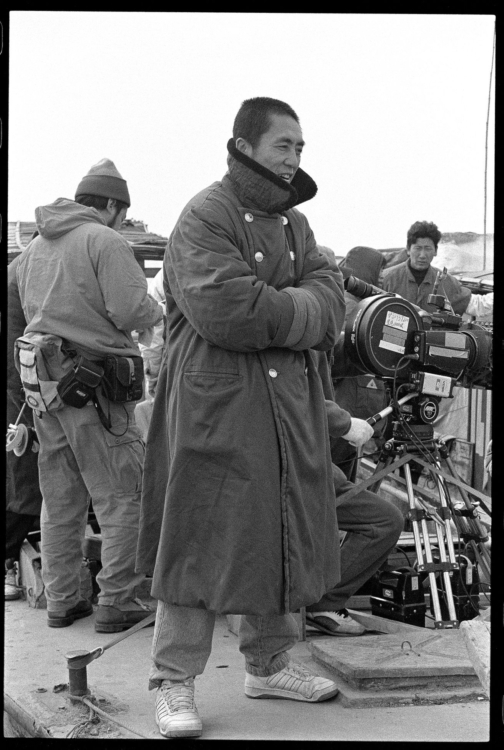

The generation that Xiao Quan capture on his photographs as a young man is growing older, but they can still be heard. This year the author Fang Fang, a lady of retirement age, proudly stood up to a mob of zealous ultra-left patriots. The famous author Jia Pingwa has just published a new novel about how, during the student protests, the young Jia Pingwa was banned from publishing his novel about the western city of Xijing and how he was nearly corrupted by fame. And even today, young guitarists will, if asked, play Cui Jian’s songs with all their heart and get half the bar to dance alone. In fact, Cui Jian supposedly said, “Don’t you tell me that you’re a different generation. As long as Mao’s portrait continues to hang over the Gate of Heavenly Peace, we are all one and the same generation.”